Parinda Sakdanaraseth

The Future of Ritual: Joss paper culture in Thailand

Summary

The project explores the future of Joss paper tradition in Thailand, using speculative lens looks into its future to find the possible alternatives for the tradition through workshops and co-design experiments. This projects also highlights its current problematic issues to environment due to social changes of value.

Additional info

This is a practice-led project that focuses on discovering what the problematic joss paper tradition in Thailand could be in the future using speculative design prospects (Dunne & Raby, 2013). This project will also explore and disseminate the current Thai-Chinese descendent opinions towards joss paper through visual ethnography on social media (Pink, 2001), including an auto-ethnography of my own experience as a Chinese descendent (Bochner & Ellis, 2016). Furthermore, it will propose an alternative to the joss paper with a co-design experiment (Manzini, 2015), using my insights as a designer to co-create a new ritual through surveys and interviews with Thai-Chinese families that is more suitable for the changes of social values.

The Past - from real things to burning paper

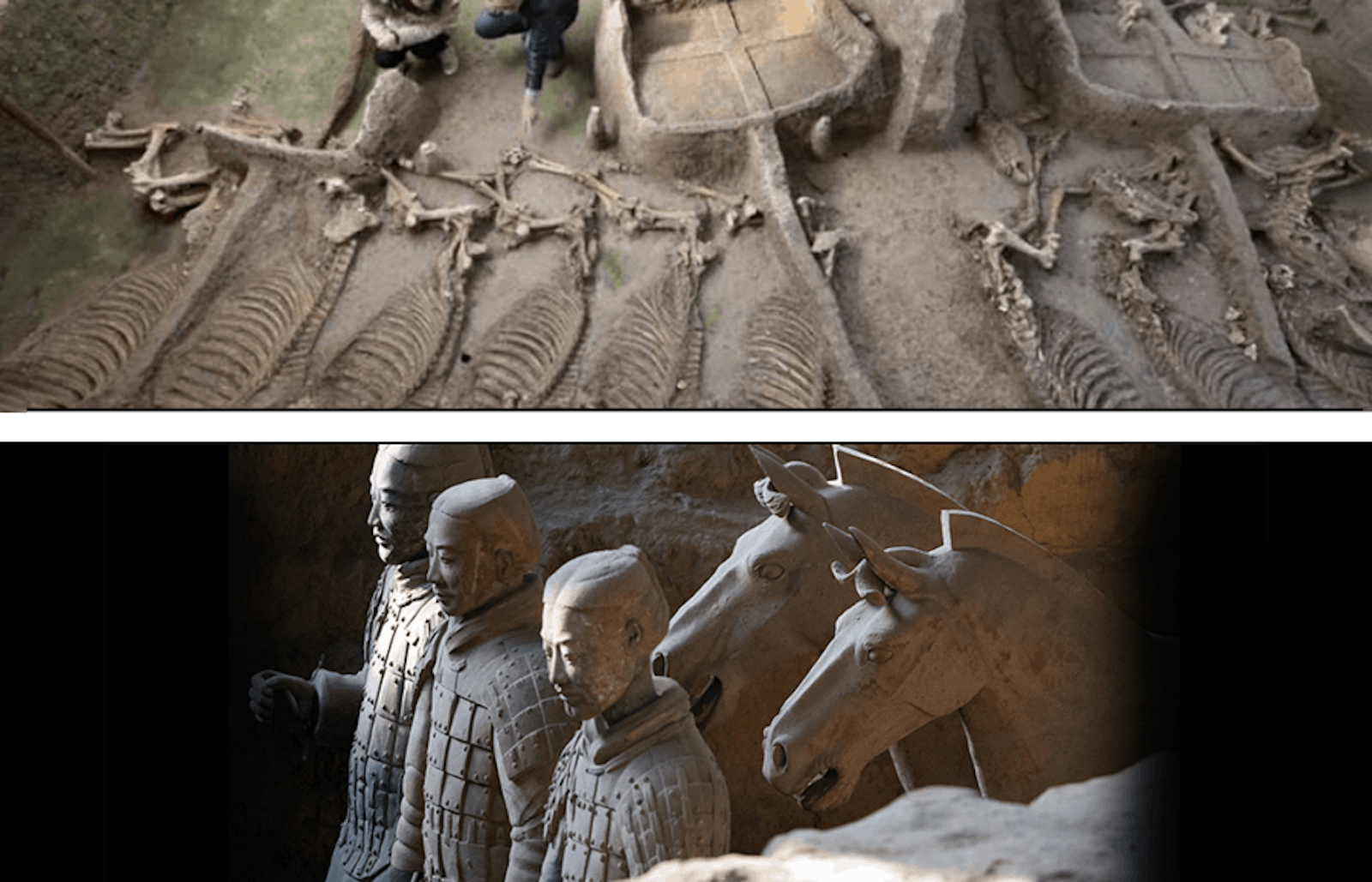

The joss paper ritual or ritual paper offerings are typical, everyday Chinese practices that can be traced back to more than 3,000 years ago. Joss paper, or ghost money, sometimes called spiritual paper, are objects made from paper and used as offerings to beings in another dimension, namely the gods, the ghosts, and the ancestors (Blake, 2011). The offeror has to burn specially designed paper to send those offerings to the offerees in the afterlife. The ritual is used for every important Chinese event in the lunar calendar throughout the year, including Chinese New Year, the Qingming Festival, also known as the Tomb Visiting Festival, and the Autumn Festival, also known the Hungry Ghost Day (Scott, 2007).

The practice is not restricted only to special events of the lunar calendar but also can be used for a personal concern. It is not uncommon to burn joss paper when you start a new business to get a blessing from gods and ancestors to help the business go well. Some use the offerings as a bargain with the gods when visiting Chinese shrines or temples, asking for a new job or a good score on an exam at school (Scott, 2007). Joss paper can be used for multiple purposes and blended in everyday life. It is used as a link to connect the living world with the afterlife, to remember your deceased family members and pay respect to the local gods. This practice can be found in most Chinese communities across the globe. Before it became joss paper as it is today, it evolved over thousands of years.

The Present - The problematic ritual

Environmental impact

One of the main concerns that have been raised and discussed widely among new Chinese descendent communities is the environmental impact of burning joss paper. It is undeniable that the result of burning, whether it is paper or not, generates smoke, which contributes to air pollution. The current joss paper that is used widely in the market is made from a cardboard paper, printed in full colours, made into offering shapes like clothes, cars, houses, or phones. Another more classic one is made from a thin sheet of cheap bamboo paper, glued with a gold and silver foil sheet component. The latter kind of joss paper generates more toxic pollution, as silver or gold foil sheets are made of toxic metallic elements (Khezri et al., 2015). Ten major elements that are found in Joss paper (Al, Ca, Cu, Fe, K, Mg, Na, Pb, Sr, and Zn) are partly released in small particles during the burning process, which causes critical damage to air quality. Moreover, people tend to forget the harm of the bottom ashes, the remaining product from burning joss paper. These ashes are often treated as landfill, and those metallic elements leftover from burning contaminate the groundwater and harm all living things (Hsin et al., 2011).

Urbanisation and contemporary lifestyle

In 1822, the population of Bangkok was estimated to be 50,000 or less. It grew rapidly due to industrialisation and urbanisation, turning the area from floating villages to a metropolis with almost one-third of a million people in the city by the end of the nineteenth century. Bangkok has witnessed an exponential increase in population from 5.2 million in 1947 to 10.5 million in 2020 (World Population Review, 2020). The city has become larger, and its population is now 210 times greater than it was in the eighteenth century. Bangkok used to be smaller, much less crowded, and surrounded by low-rise buildings. The modern Bangkok now is a much bigger city, much more crowded, and full of high-rise buildings. The overpopulation and industrialisation have made air pollution a major issue for Bangkok. Modern Bangkok is no longer convenient for joss paper burning.

Everything changes when the pandemic hits

At the beginning of 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic, which originated from Wuhan, China, hit. It has affected every aspect of our lives across the globe. Globalisation makes COVID-19 worse than any virus outbreak we have experienced before. Social distancing and wearing a mask has become a new normal that everyone has to comply with until we discover a vaccine for the virus.

Thailand was the first country to have a positive COVID-19 case outside China. By March, when WHO officially announced COVID-19 as a pandemic, the confirmed positive cases were up to more than 1,600 (World Health Organisation, 2020). Like other countries, everyone came to practice social distancing, avoiding mass gatherings and travelling during that time. The Tomb Visiting festival, which is considered one of the main events that occur around the beginning of April, according to the Lunar calendar, was also cancelled for Chinese descendants in Thailand. How can we practice the tradition when we are not allowed any human and social interaction? How can we keep our families connected when we are forced to be physically disconnected?

The future - An alternative now for the ritual

What if…? exploration

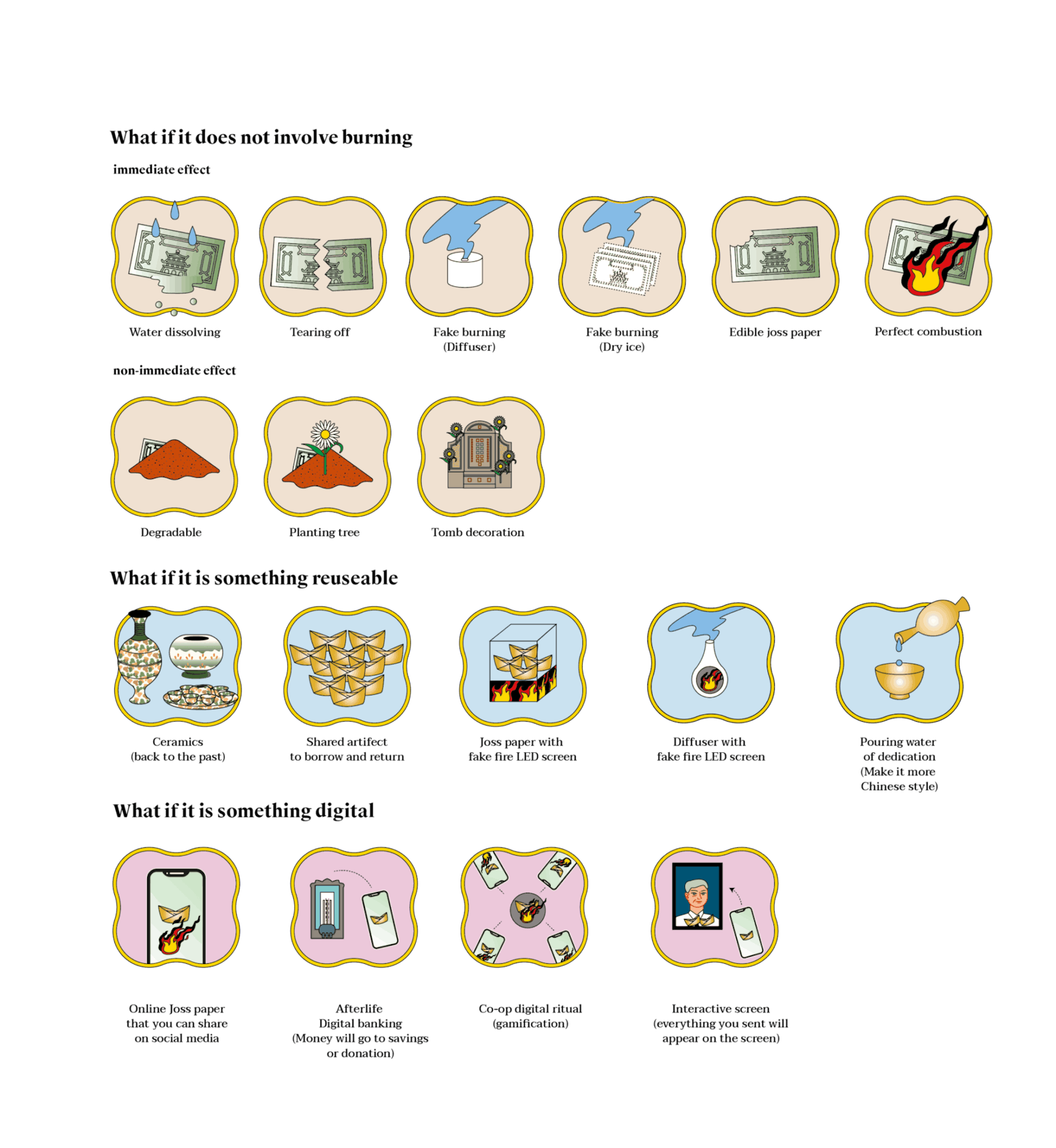

I used “What if” prompts as a starting point to explore the idea for alternative joss paper by asking myself three questions about scenarios: “What if it does not involve burning?” “What if it is something that can be reusable?” and “What if something is digital?” I began to sketch out my idea, as much as I could, to respond to those questions. Perhaps instead of burning, the joss paper could be dissolved in water? Maybe it could be eaten? Could it be a set of artefacts that could be reused every year? Or perhaps it could be a co-op digital ritual in which you need to cooperate with family by mobile phone to complete it? I sketched those ideas quickly into my notebooks then realised it would be hard to explain these ideas to other people, as some are quite complex. I decided to visualise these explorations in a set of illustrations, categorised by “what if” questions for use in the next step,

sharing the ideas and co-designing the ritual with other joss paper practitioners.

Co-design experiment

Before doing an experiment with my family, I prepared the card set, using the illustration I did before for every eight options that I got from scoring. I created an additional two cards to represent the ritual process, offering period and transmission period, and another two to describe the place that the ritual might occur; home and the tomb. I chose the study room in my own house as a place to conduct the experiment, then set a camera to record the whole conversation. I was sitting in the middle while my parents sat on one side, and my siblings sat on the other. I quickly walked through my research project, the history of joss paper, and its problematic issues. I also clearly stated the objective of this workshop was that we would create a new joss paper ritual that will be used on this coming Autumn festival (September 2, 2020, and the experiment was conducted on August 1). After the introduction, I started the conversation by putting down one of the option cards, randomly, and put the ritual process cards and the place cards around them before asking them what score they would give and why. Could they imagine what would happen during the ritual or at those places? The cards worked well as a dialogue generator. After demonstrating the first card, for the next option card I put down, my parents and siblings started to argue their opinions and discuss their ideas automatically. They used the cards to refer to their ideas, saying, “I like this one better than this one (pointing at the cards)” and even suggesting, “I think this one could be put together with this one (putting cards together). That would do for me.”

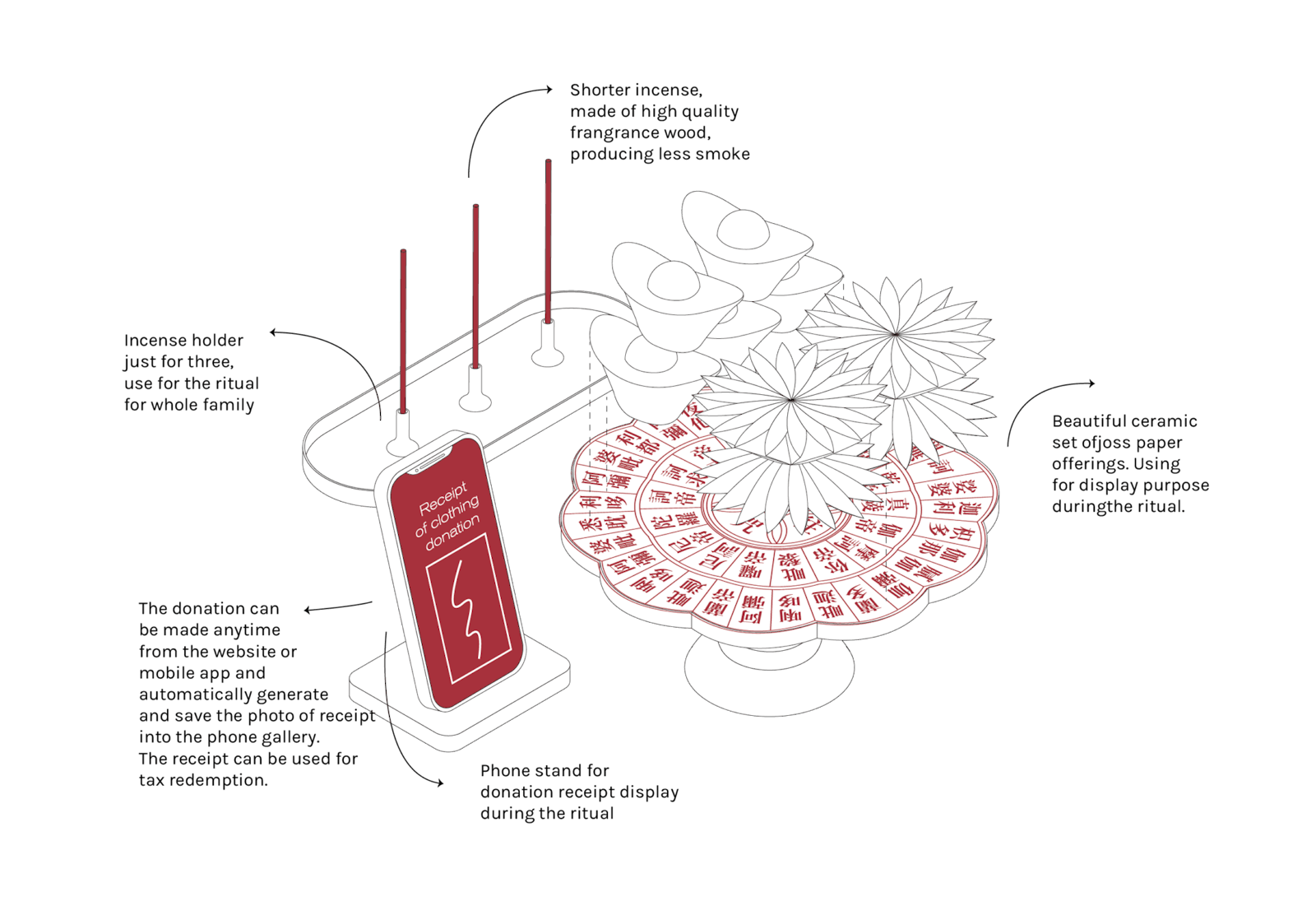

After walking through all the options cards, I asked them to rank the best options for them. Three cards, which are “Ceramics joss paper that can be reusable every year,” “Afterlife banking services where money will go to donation or savings,” and “Diffuser with fake fire screen” emerged from the discussion. The first two are the essential set that we all agreed was the best solution. The ceramic joss paper is the offering period, for putting among food offerings to fulfil the desire for a complete picture of the original ritual. The second is for “paying respect” or “transferring the merit” to the dead. Instead of burning the fake money, the real money will go to a donation to be used in the name of the deceased family members. These two are a must, and all family members were all content with the choices. The last one, which is “Diffuser with fake fire screen,” is nice to have but not necessary. It would be great if it replaced joss sticks, creating an aroma, especially at the shrine where the massive joss sticks and candles will be lit. My parents, who I thought would be against completely dismissing the burning process, said that with the donation, they were happy to do it, as they liked the idea of donating money in the name of our grandparents. They believe they will receive these “good deeds,” which is better than money in the afterlife. The ceramic joss paper will be just for the aesthetic visual while doing the ritual in front of the tomb or the deceased avatar, which they do not mind reusing every year. To make the picture of ritual clearer, I did a rapid sketch of what I intended to do and would happen at the coming Autumn festival. My mother even offered to go shopping to make an offering set with me at the Chinese antique store.