Telle Yang

Myth Now: An exploration of the use and function of myth and metamorphosis within contemporary art

Summary

Combining reflective art practice, storytelling, and psychogeography, this practice-based research explores the non-linear strategies used within contemporary practice. It connects culturally and temporally diverse stories of our existence beyond the human to make sense of the present and imagine different future possibilities. The spatial practice that sets sculptural components in a dialogue with paintings together speaks to:

- Engaging with the concept of metamorphosis, what can a cross-cultural, multisensory mixed-media contemporary art practice gain from myth, and the process of myth-making?

- How does such working across cultures and time speak to contemporary ecological and existential crises?

Additional info

Telle Yang is a multimedia artist currently based in London. Her research and practice explore cross-cultural myths and metamorphosis through storytelling and psychogeography, responding to ecological entanglement and existential concerns. Working with clay-based sculptural installations and mixing the use of natural and reflective materials to perform her writings, she wants to create a space that enables both her works and audiences to breathe. Blurring the boundaries, audiences are brought in as participants, resonating with the mythological time and space through interactive field creations. The recurring clay refers to the Chinese mythology, Nüwa Created Humanity, in which the mother goddess made humans out of clay. The materials are transformed as narrative carriers actively participating in metamorphic myth-making. Before joining MRes RCA, Yang was awarded the degree of Bachelor of Arts with first-class honours in Fine Art from the University of the Arts London in 2023. She obtained her MA in Contemporary Art Practice from the Royal College of Art in 2024, and she has had her group show at the Tate Modern in London, collaborating with Montez Press Radio and Tate Lates. Her work Stretch Out is selected on the shortlist for the ‘Inspiration from the Elements Art Competition 2024’ and is part of the virtual exhibition online in 2025.

Abstract

Myth-making has re-emerged as a vital strategy in contemporary fine art. It allows artists to address urgent questions of identity, environment, and society through ancient narratives of transformation. This practice-based research explores how and why artists today draw upon mythic metamorphosis across cultures and time to speak to the present moment. It asks how myth in art is being mobilized to explore our contemporary condition, and how textual mythological narratives can be translated into multi-sensory, mixed-media art practice with perceptual interaction and spatial immersion. Drawing upon literature and critical theory such as Donna Haraway’s ‘Tentacular Thinking’, Jane Bennett’s ‘Thing-power’, and David Burrows & Simon O’Sullivan’s ‘Re-mythologizing’ and ‘Fictioning’, the text interweaves analysis with a reflective account of my artistic process.

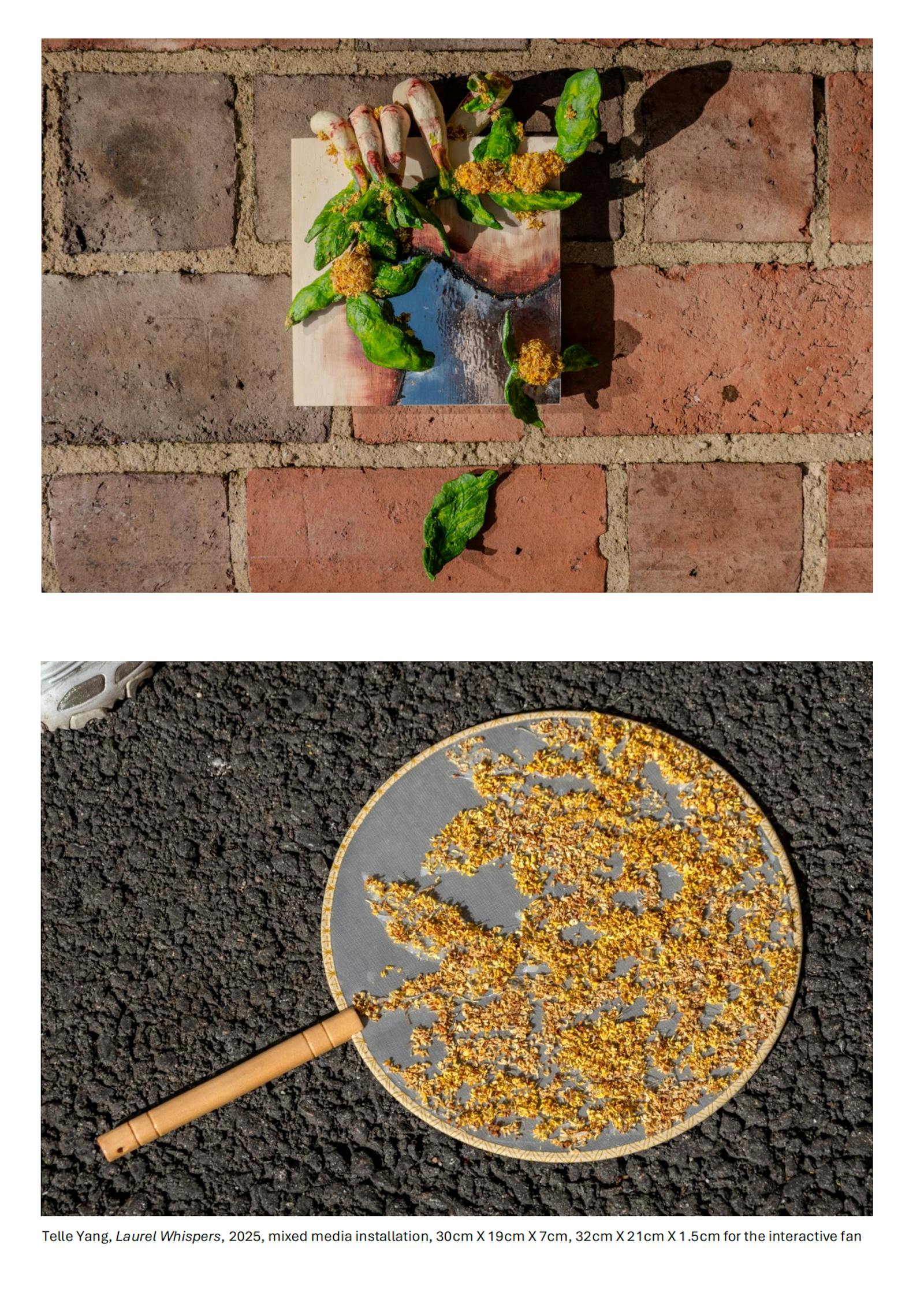

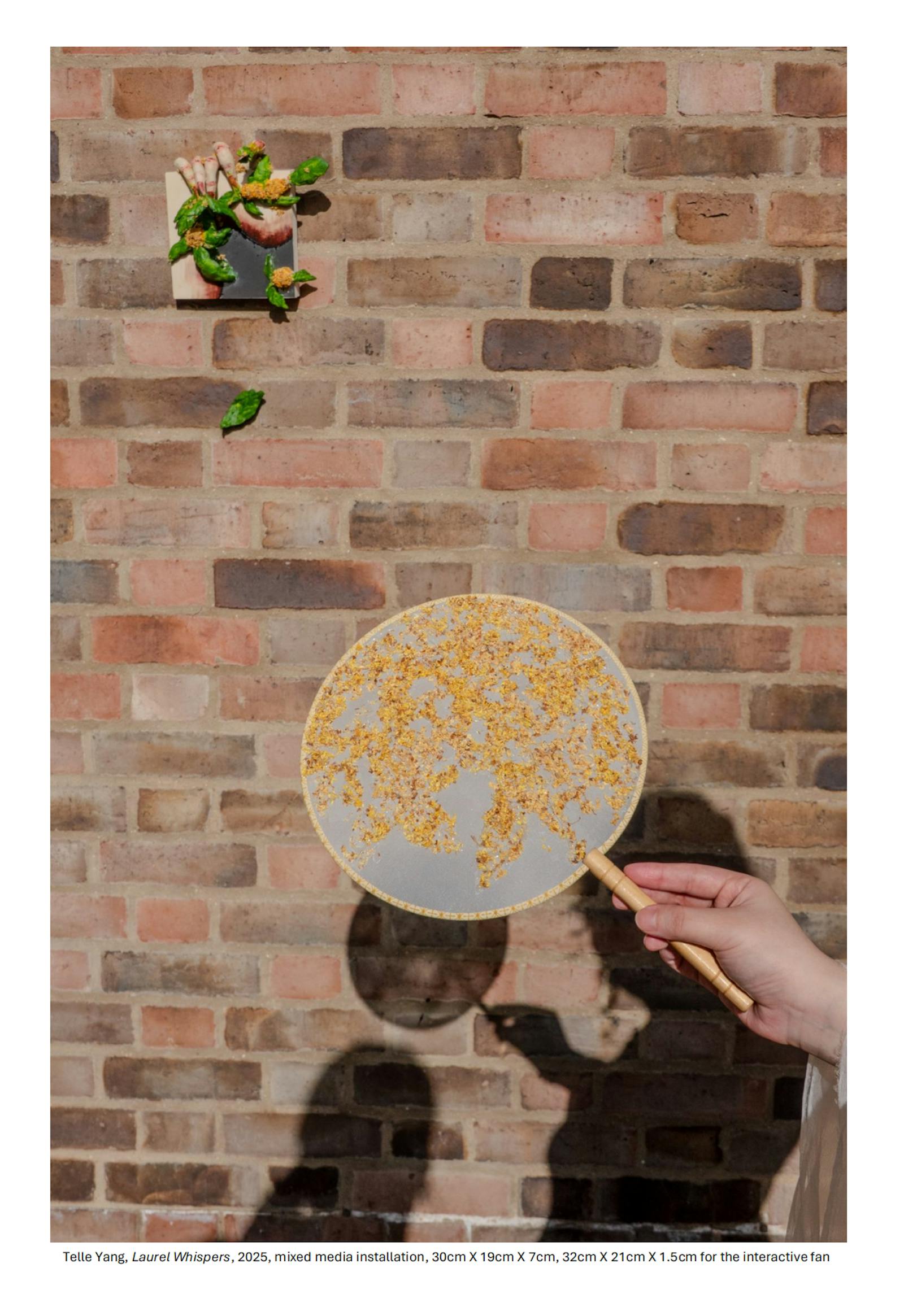

My practice developed from a reading of the story of Daphne and Apollo, from Ovid’s Metamorphoses (1955) which draws heavily from the Greek classical tradition and Roman cultural influences. I entwined this Greek myth with Chinese folklore, specifically the character of Wu Gang[1], the immortal condemned to endlessly fell a regenerating osmanthus tree on the moon. In my story, the Western laurel tree, which was born of Daphne’s metamorphosis, meets the Chinese osmanthus, a tree from both Wu Gang’s tale and my own childhood, creating a cross-cultural myth of metamorphosis. This narrative became the foundation for a multi-sensory body of work: highly scented, shadow-recordings on traditional Suzhou silk fans dusted with dried osmanthus flowers; tactile air-dry clay sculptures inspired by the Chinese creation goddess Nüwa[2]; and layered acrylic paintings on wood with reflective vinyl. These elements form an installation that blurs the boundaries between painting and sculpture, myth and material, story, and an audience which not only sees and feels but smells, too. Through its own cross-cultural mythic metamorphosis, the work invites viewers into an immersive, sensory and affect-rich environment where ancient classical myths are experienced in the here and now.

[1] Known for the story of ‘Wu Gang Chopping the Tree’, a Chinese folk myth associated with the Mid-Autumn Festival and lunar mythology, dates back to at least the Tang dynasty. The tree ‘guì’ referred to both the laurel and the osmanthus.

[2] Known for the Chinese mythology ‘Nüwa Created Humanity’, the mother goddess made humans out of clay.

THINKING THROUGH THINGS

A crucial aspect of this mythic reappearance and growth is the emphasis on materiality and the senses. It is the translation of narrative into tangible experience. Here, Jane Bennett’s concept of ‘Thing-power’ is illuminating. In Vibrant matter: A political ecology of things (2010), Bennett argues that objects and materials are not inert props for human stories, but active participants with their own energies. In mythic art, this concept infuses works with a presence that can speak beyond the artist’s intentions. Many contemporary myth-inspired installations contain the agency of materials. Thinking of the synthetic fabrics, foams, and glittering surfaces in Shani’s DC: Semiramis (2019), and the soil, audio recordings, and scented air in Prouvost’s Above Front Tears Nest in South (2023). Such elements possess a sensuous quality where they seduce the viewer’s touch, smell, and embodied memory, thereby enacting the myth in the register of physical sensation.

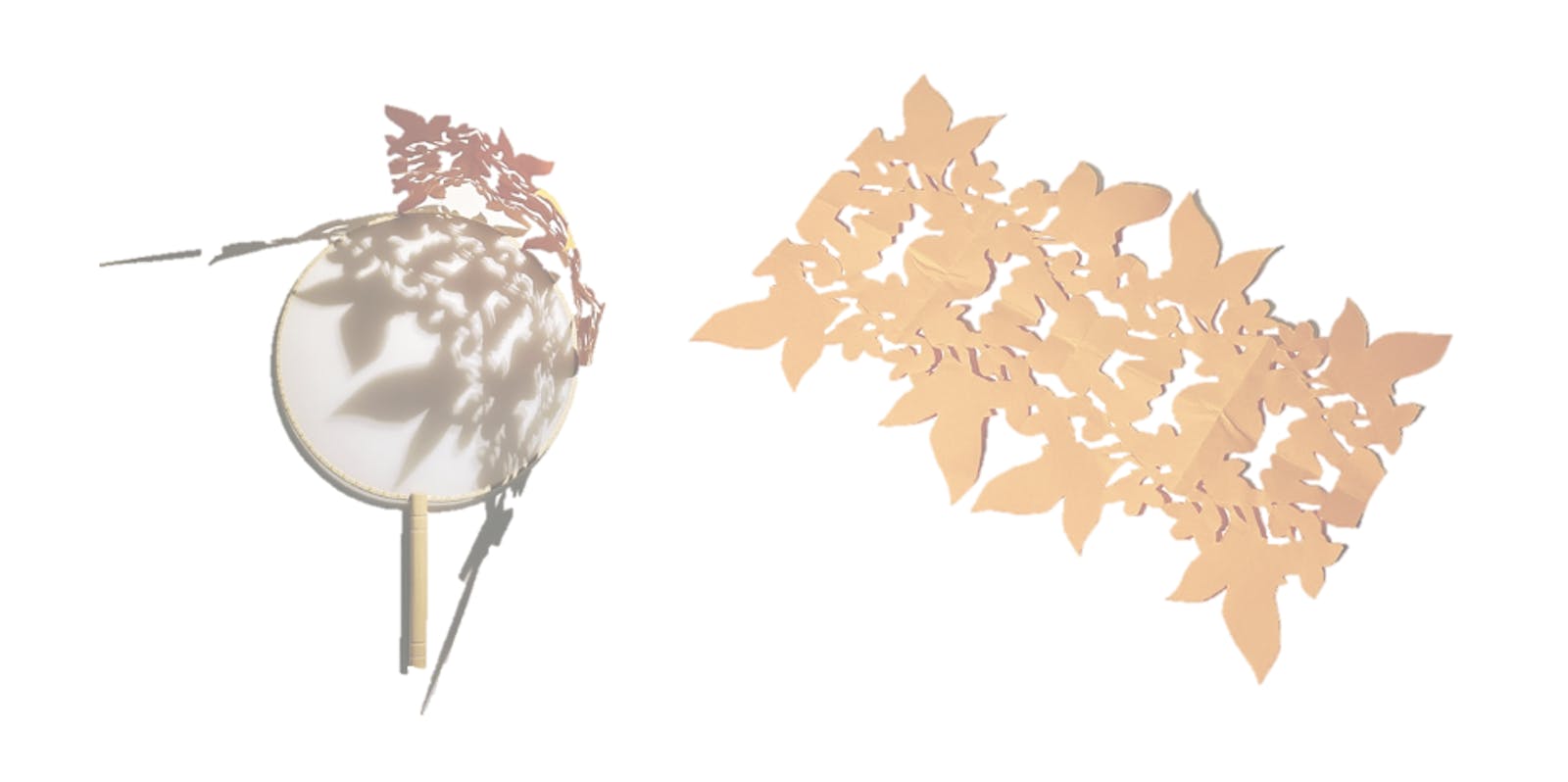

In my practice, materials were chosen for their symbolic and sensory influence. The Suzhou silk fans, for instance, carry the cultural history of a traditional Chinese craft associated with storytelling and a tactile delicacy. By recording shadows on silk fan surfaces that ephemeral imprints of moving forms, I evoke the transient moment of metamorphosis, as when Daphne’s body dissolves into bark and leaves. The fans, when handled, also produce a faint breeze and sound, activating touch and hearing. Dried osmanthus flowers are stuck on these fans. Their natural fragrance scents the installation, engaging smell as a narrative device like a sense of autumn that bridges to Wu Gang’s eternal osmanthus tree. These tiny golden blossoms, preserved from decay, themselves symbolise suspended time, much like myth holds moments in eternal pause. The air-dry clay sculptures take on the role of Bennett’s ‘vibrant matter’ (2010). Clay, as the substance from which Nüwa molded human bodies in Chinese myth, here becomes the medium for hybrid figures of human and tree. As I shaped these pieces, I conceived of the clay as a creative force from the beginning of the world and an echo of Nüwa’s own hands. The finished small entwined sculptural forms, where limbs sprout into branches and laurel leaves, invite viewers to consider the blurred boundaries. They are deliberately left with the raw texture of hand-formed clay, emphasising the earthy quality. This is in line with Haraway’s tentacular ethos of ‘making kin’ with nonhuman nature (2016). The sculptures are materially kin to soil and flora, not fully refined into high art objects.

By foregrounding materials, the work supports that the myth is not only represented but incarnated in materials that carry their own stories and agency. A fan or a flower is not just a symbol of a mythic tree, but a fragment of nature with which the audience can form a direct sensory relationship. The rustle of silk or a waft of osmanthus can trigger memory and emotion in unpredictable ways, allowing the installation to exceed the narrative and present the active participation of nonhuman forces. This approach transforms the myth from a textual tale into a perceptual event. The audience does not just read or view the story of metamorphosis. They smell it, touch it, and even breathe it in. Such multi-sensory engagement can produce an intimate form of understanding of a kind of knowing by feel that adds to the intellectual and visual experience. It speaks to the way of thinking through touch and material specificity, showing how narrative knowledge can be embodied and affectively transmitted.

BEYOND THE TEXT; ENTANGLED REALMS

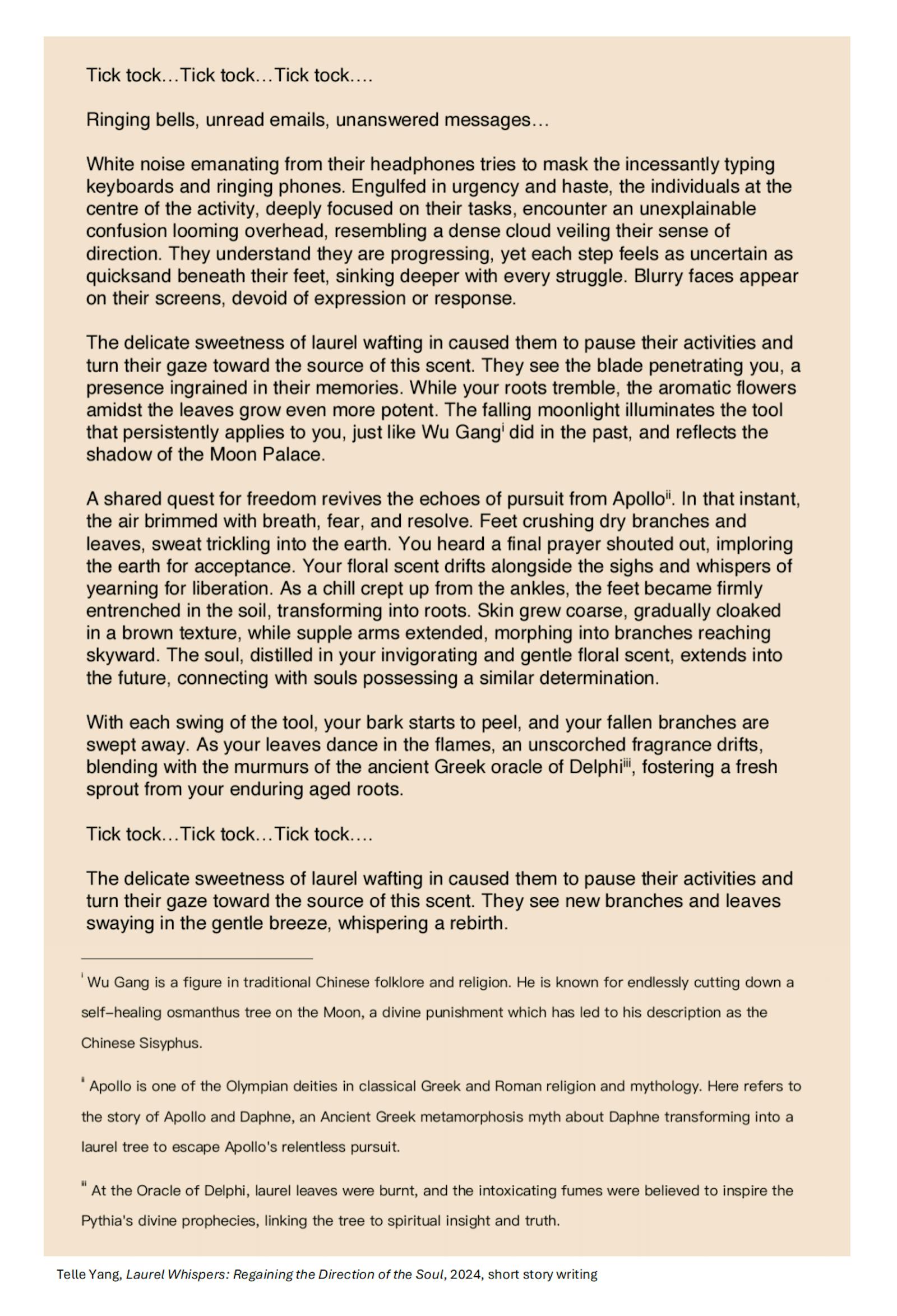

Transforming a written mythological story into a multisensory mixed-media installation is a process of translation not only between senses and mediums, but also between modes of thinking. With reflective artistic practice, storytelling and psychogeography as my key methodologies, this research journey began with a piece of writing that merged myths from different places into one short story. The story Laurel Whispers: Regaining the Direction of the Soul, revolves around white noise and the scent of laurel/osmanthus, connecting present confusion and anxiety with mythological fables, and personal awakening. It reflects how a contemporary person in the here and now might gain healing and spiritual enlightenment by thinking about myth and by engaging with myth.

In my storytelling, the narrative person changes from the third-person ‘they’ to the second-person ‘you’, then back to the third-person ‘they’. Without naming any characters or clarifying gender and identity specifically, readers are more encouraged to immerse themselves in their own experiences. This narrative style avoids gender stereotypes or limitations imposed by specific socio-cultural backgrounds, reflecting a broader range of shared human experiences. Readers can easily put themselves into the existential concerns faced by any ordinary individual in contemporary society at the beginning of the story. Subsequently, the attention shifts to a non-human perspective of the laurel/osmanthus, experiencing both physical and mental metamorphosis through the combination of spirit and nature. The perspective from the story finally returns to the beginning is not only a structural completeness, but also symbolises the narrative themes of life, anxiety, liberation, and rebirth, which are constantly repeated in a cycle. Everyone may experience similar spiritual loss and awakening, and the dilemma of life and the desire for freedom will continue to repeat themselves.

Writing from different perspectives in a poetic and non-linear narrative mode with multisensory descriptions and a circular narrative structure helps me challenge anthropocentrism. This worldview separates human beings from and superior to the non-human world, structures time linearly, placing vision and cognition at the top of a sensory hierarchy, and privileges language and consciousness as human traits. Through narrating non-humans and speaking from the perspective of a laurel/osmanthus tree in the second person ‘you’, readers are pushed to experience the world from a non-human angle. The rich sensory details, such as smell (the fragrance of laurel), touch (the blending of roots and soil), hearing (the whispers of leaves), etc., also help readers break through pure rationality and logical thinking, while highlighting interspecies entanglement in the fluid multi-angle narrative. In addition, the narrative finished in a way that connects back to the beginning, reflects the cycle of life and nature, and breaks the human-centric thinking of linear progress. The narrative transition between ‘you’ as the laurel/osmanthus tree and ‘them’ as working people in the story highlights plants as active life forms rather than mere tools or backgrounds. Thus, this storytelling technique shows the profound connection between humans and non-human beings, but also awakens readers to re-examine their own roles in a broader ecological community.

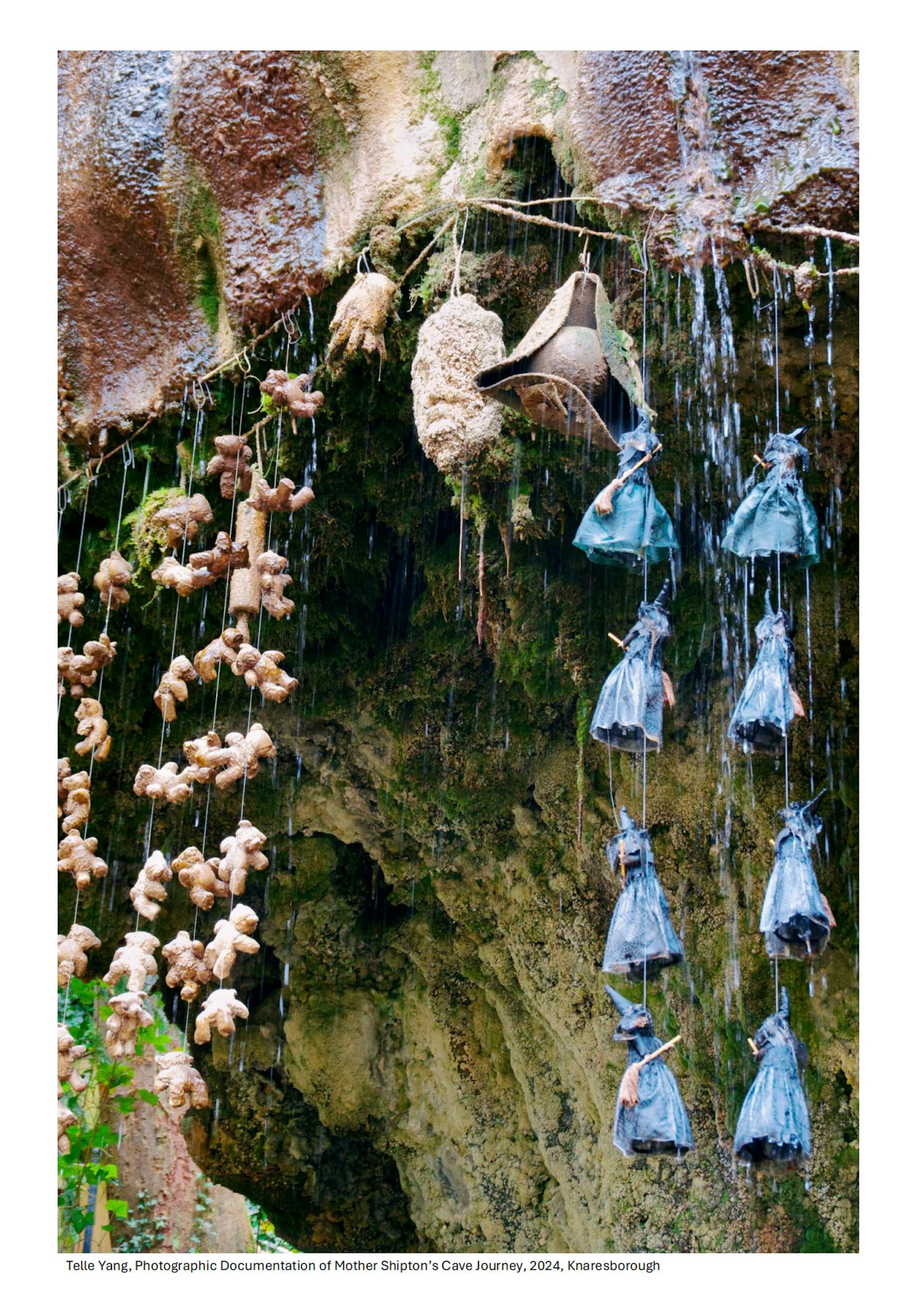

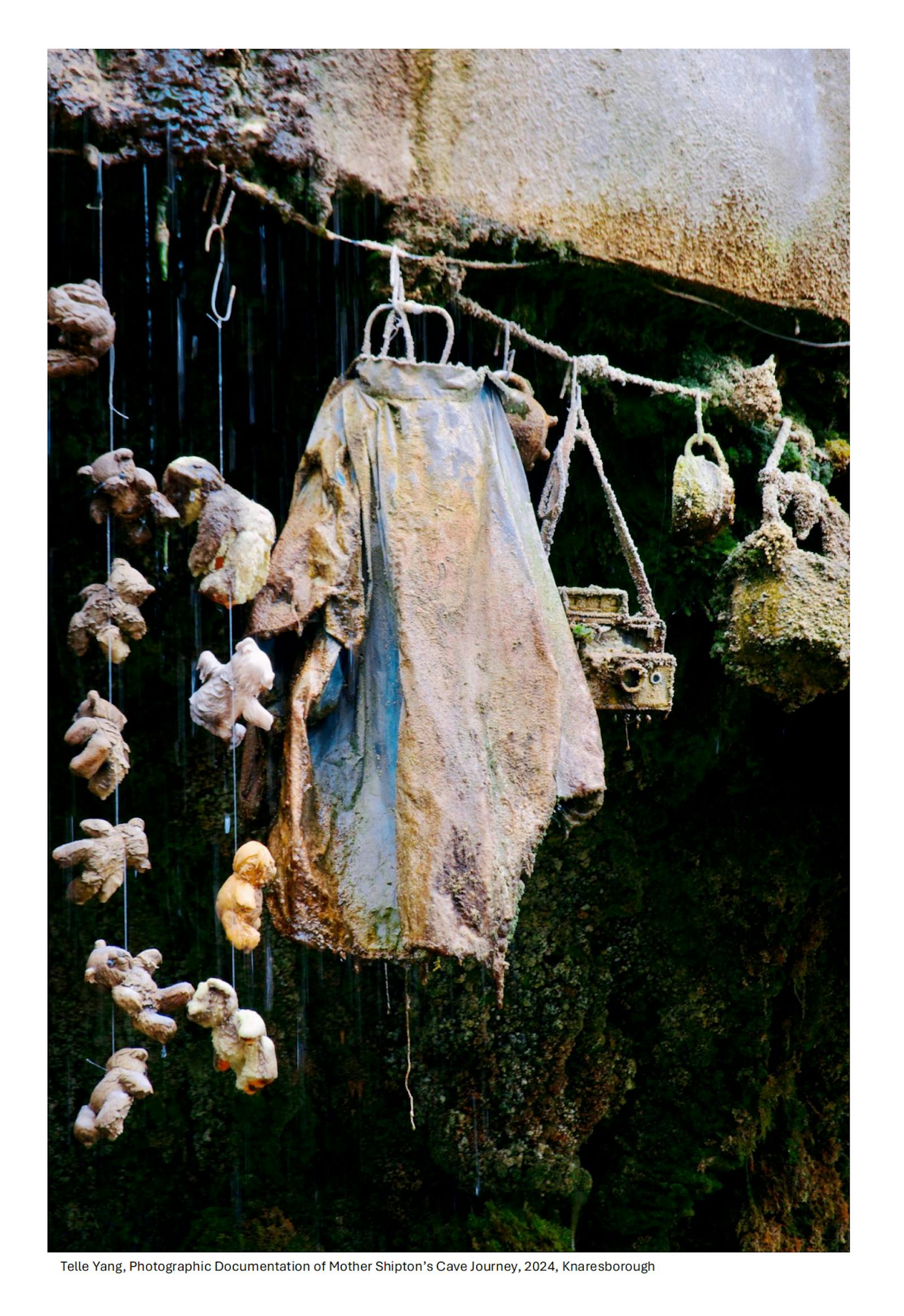

The cross-cultural dialogues between Wu Gang’s cutting down of a self-healing osmanthus tree on the moon, and Daphne’s transformation into a laurel tree to escape Apollo’s relentless pursuit of her, and the burning the laurel leaves at the Oracle of Delphi to inspire the Pythia’s divine prophecies, emphasise ‘metamorphosis’ as a way of self-renewing and self-transcending. This feels so much more productive to me than narratives of escaping from reality… As I moved from text to materials, I continually asked myself how this narrative element could be experienced, not just recounted? Psychogeography is the practical entrance into ecological and mythological imagination. The process is not only feeling the environment; it is more about establishing a physical connection between space, history, and the present, allowing artistic practice to directly absorb local narrative power. Through sketching, sculpting, annotated photography, and documenting by video during the visit to Mother Shipton’s Cave in Knaresborough, I captured the transformations between plants and humans inspired by the birthplace of England’s most famous Prophetess, Ursula Sontheil, who is known as Mother Shipton for predicting the future.

The cave itself is a place where history and mythology intertwine, filled with ecological and cultural symbols since ancient times. The Well Spring feeds the magical Petrifying Well and Wishing Well. Nearby, I can directly feel the spring water gushing out from deep underground and flowing through mineral-rich aquifers, releasing a unique scent of moisture, soil, and minerals intertwined with the rocks. The scent of the moist mineral leaves a profound impression on my sensory memory, activating associations about the cycle of life, material deformation, and ecological regeneration. The rich minerals, including the abundant calcium carbonate and smaller amounts of sodium and magnesium in the water flow, form petrification, a process of turning matter into stone. I can feel the transformation process by observing the hanging objects with minerals sticking to them and forming layers, from softness to hardness, from living to mineralisation. This journey guided me in assigning sensory media to my story, especially that of smell.

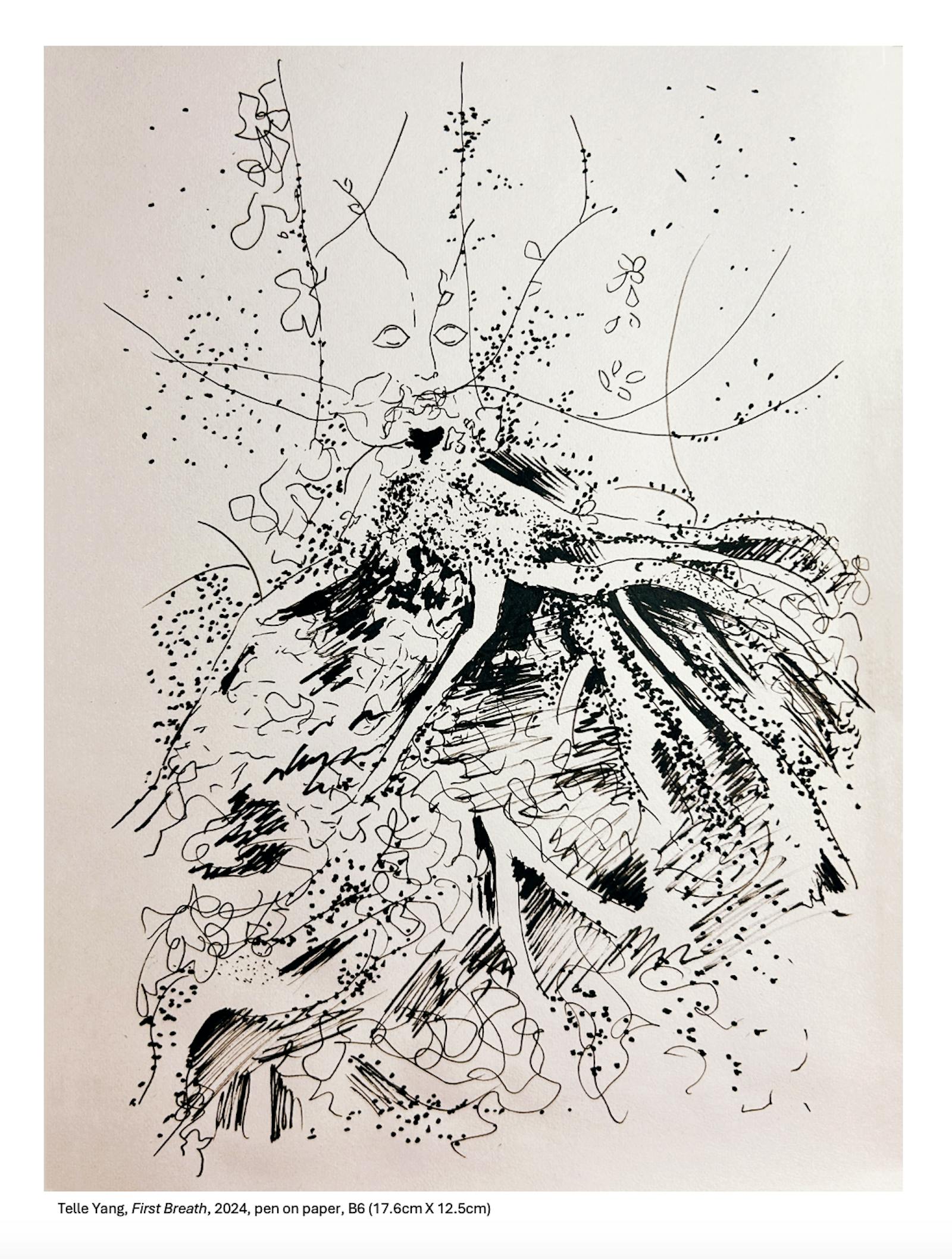

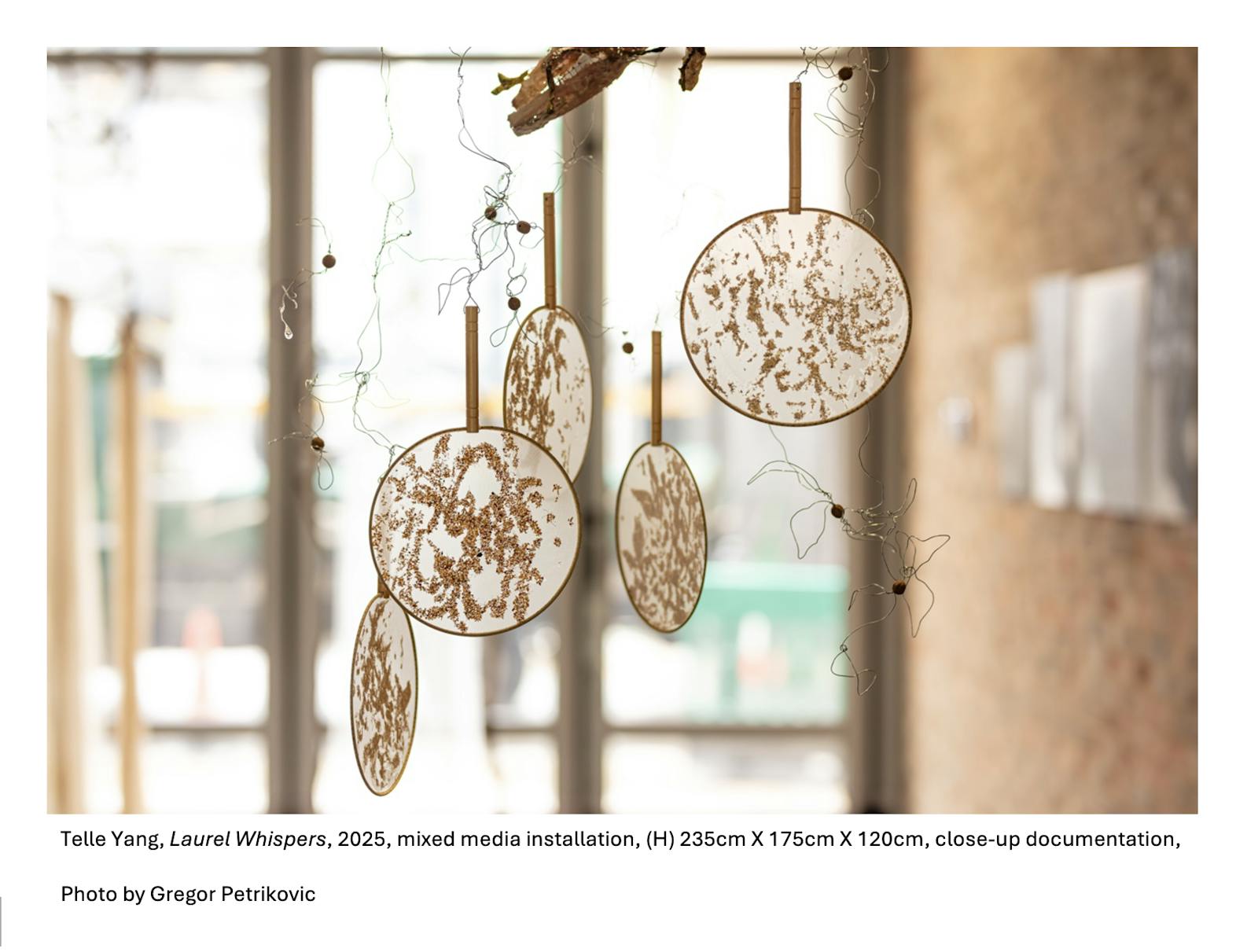

The fleeting shadow represents the instant of metamorphosis, a moment that cannot be grasped, only glimpsed. I performed the shadow recordings by placing the papercut of possible creatures from the outline of the osmanthus tree that accompanied my growth in my grandparents’ small yard between a light source and the round silk fans from my hometown, Suzhou. The silhouettes were marked on the silk surface by sticking dried osmanthus, creating a textured surface that invites touch and smell. Carrying rich cultural meanings, the fan represents the auspicious meaning of a union and happiness, similarly to the meaning behind osmanthus. Traditionally, artistic creations involve drawing, calligraphy, and embroidery. Here, the painting is done by shadow and natural elements, suggesting a collaboration between the artist and the environment. It also recalls the tentacular co-creation across species and forces. To enhance the aroma and bringing the real healing effect, these fans are hung with laurel leaf-like wires with the incense pearls I made based on the intangible cultural heritage of ancient Chinese incense-making technique. Based on the traditional osmanthus recipe, the incense pearls are fully natural and help with releasing tension, relax your mind, and calm the nerves. Memory and story are literally in the air around the viewer who is wrapped in the diffusing scent.

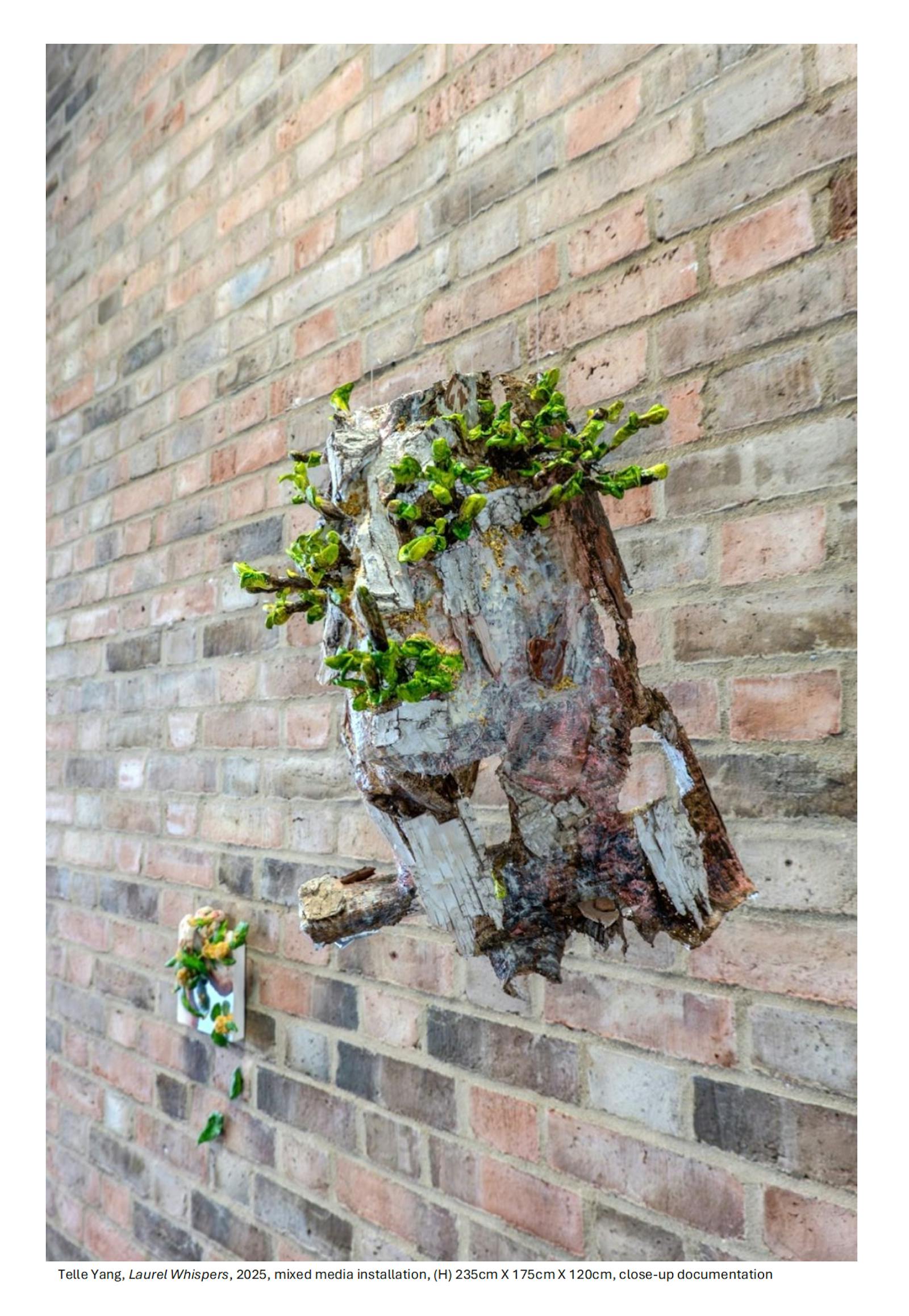

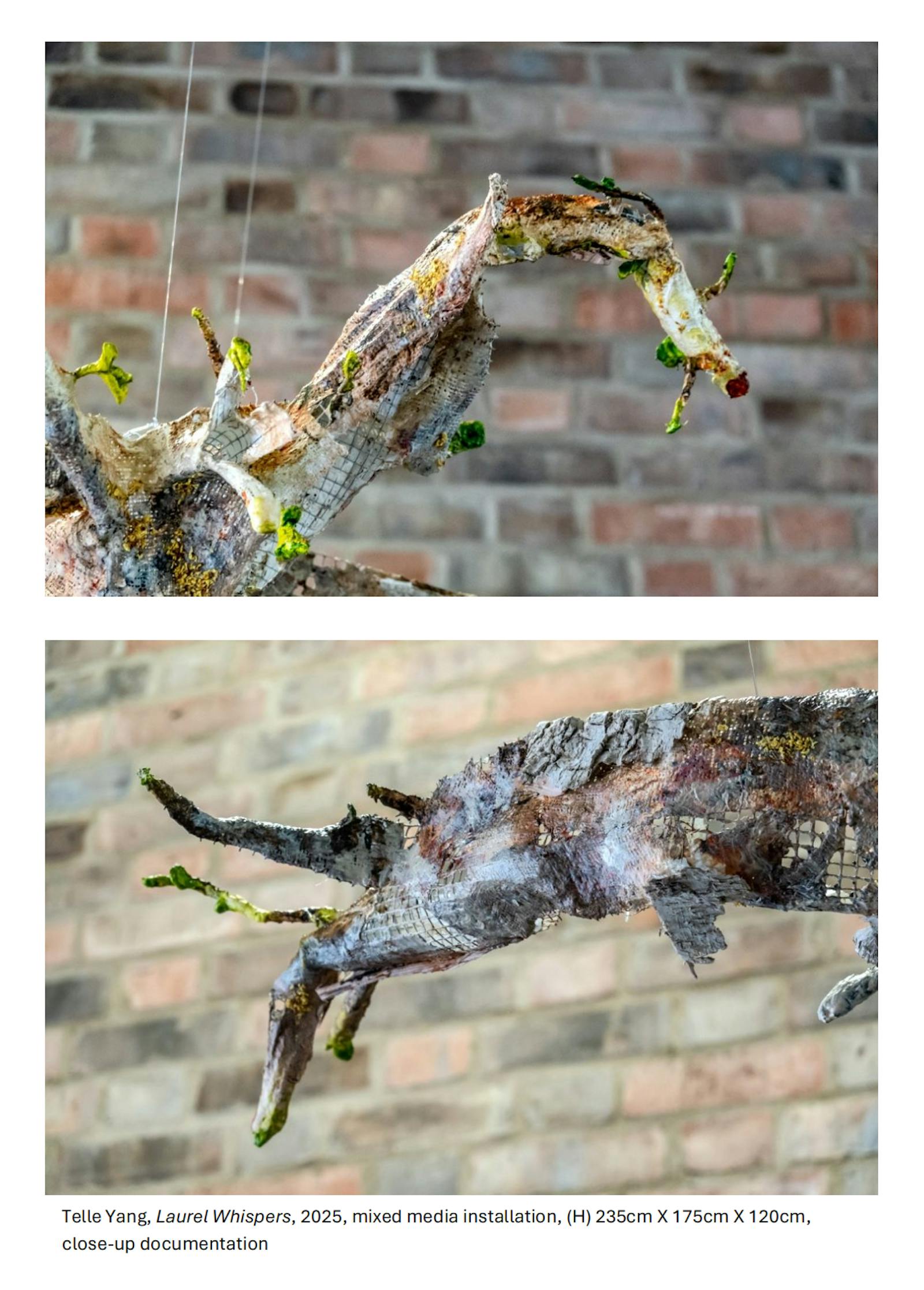

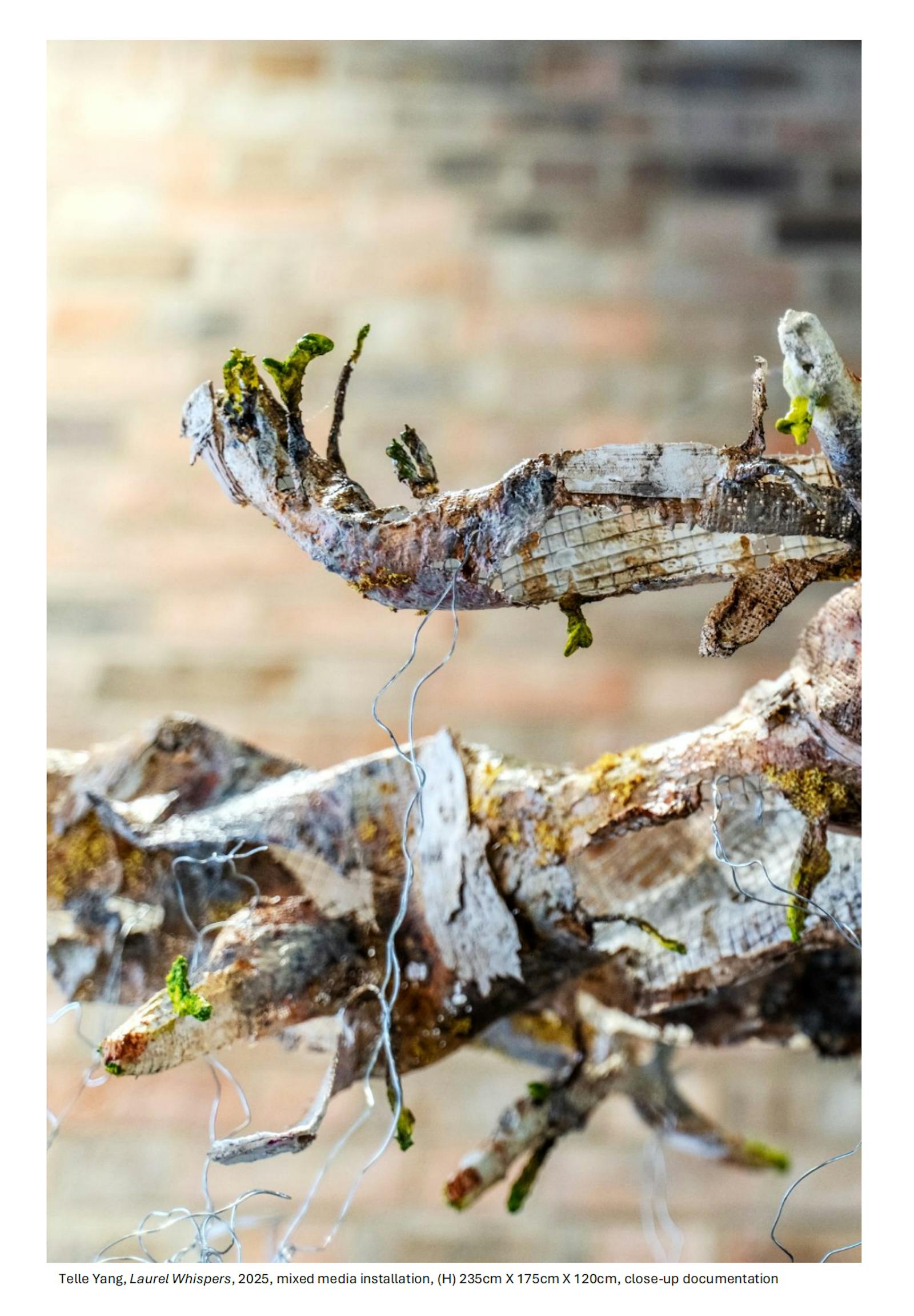

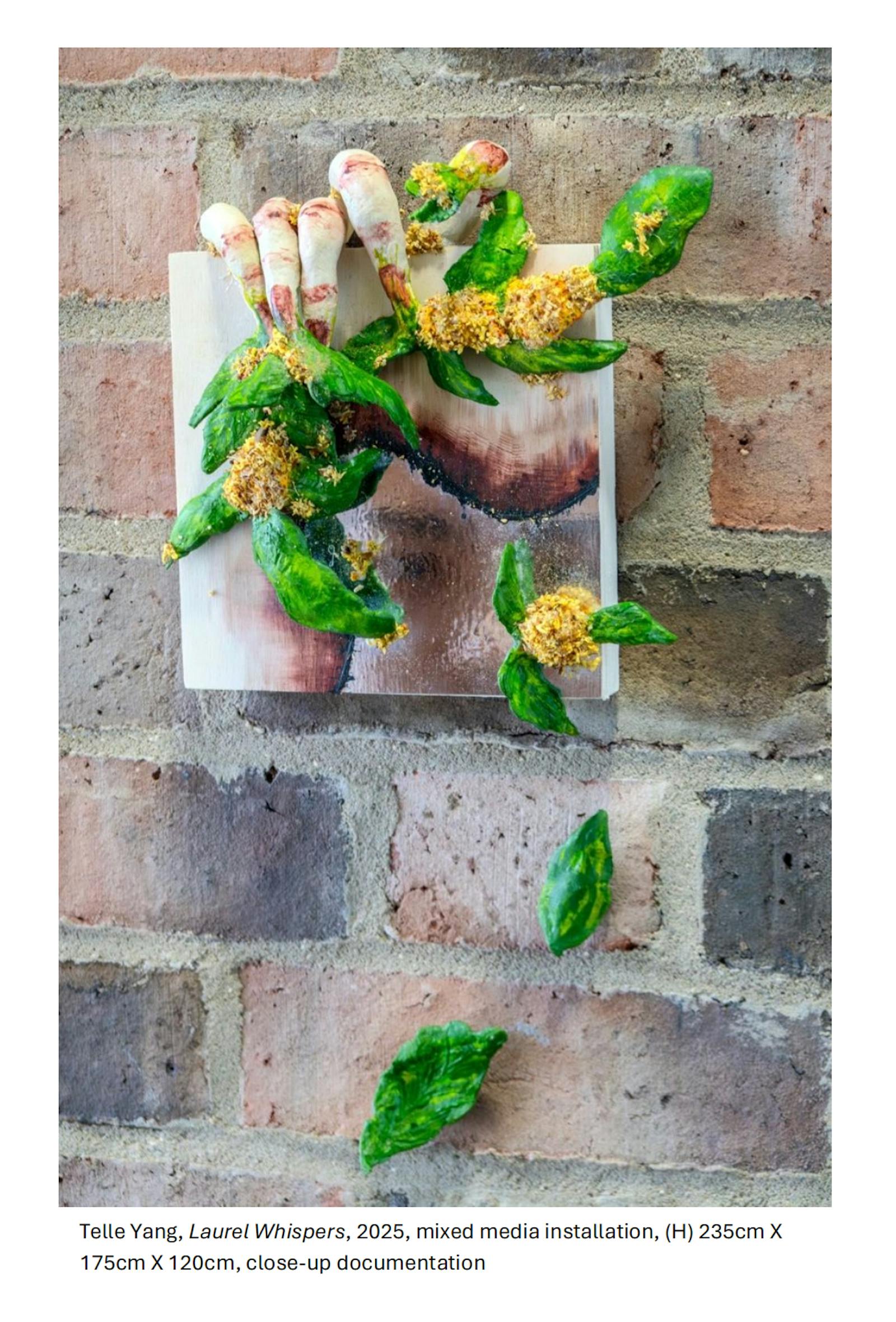

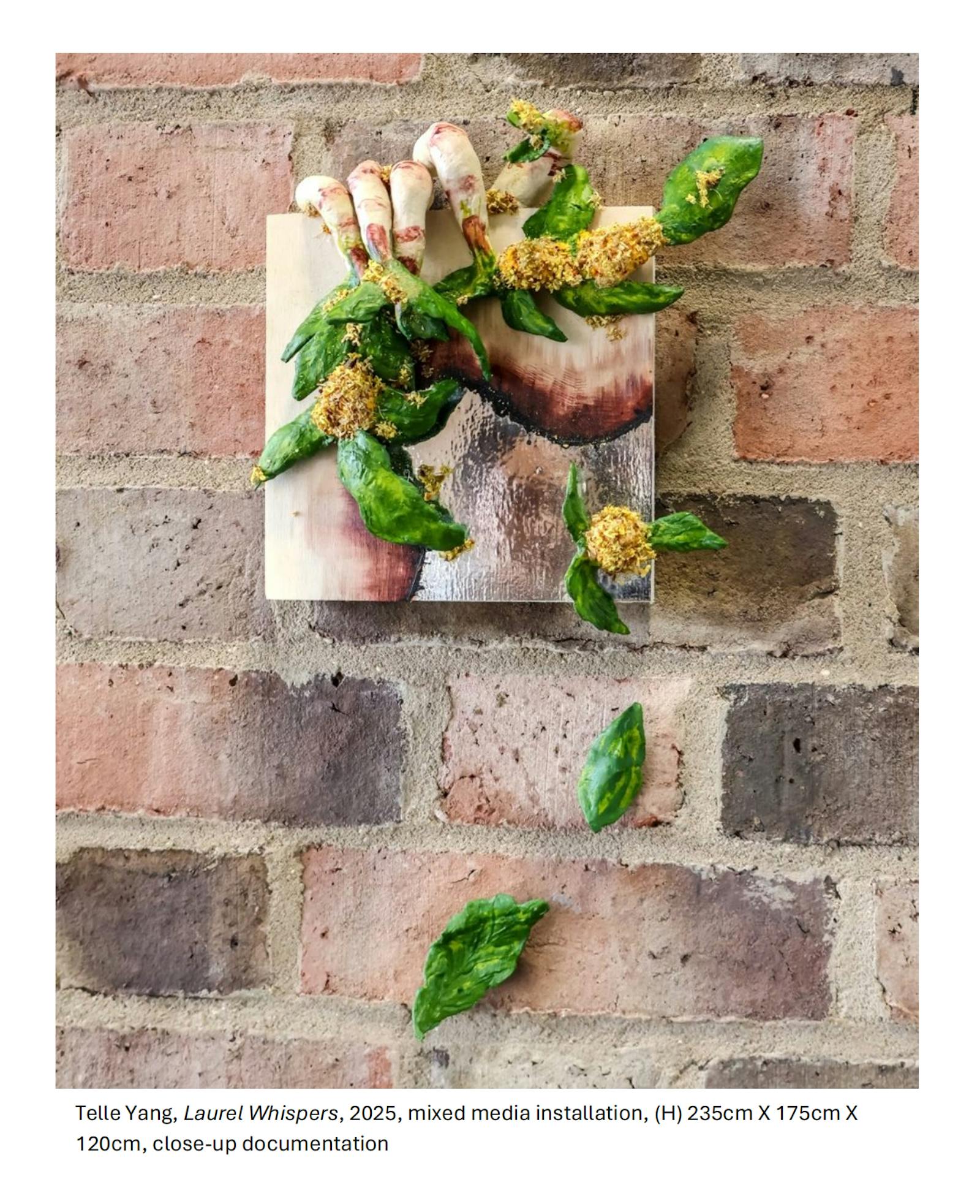

If shadows and scent evoke what is fleeting, the small clay figures ground the installation in the corporeal. Sculpting by hand was a meditative and performative act for me. I imagined Nüwa’s mythic act of moulding life while I pressed and shaped the clay. The sculptures show the human face, limb or finger morphing into a tree trunk and branch, with actual dried osmanthus petals and small bits of real tree bark embedded in the plaster and clay skin. This directly visualises metamorphosis. But importantly, the air-dry feature of the clay keeps the marks of my fingers and may develop cracks, suggesting that transformation is an ongoing, unstable process. Viewers often come closer to these sculptures, almost subconsciously desiring to touch their textured surfaces, although the fragility usually prevents actual handling. In this impulse, I see a successful translation of the power and feeling of the myth into a physical emotion for the object. The sculptures sit on the wooden panel on the brick wall or hang at various heights, so audiences can walk around to interact with them in the space.

Working collaboratively with the sculptural elements, the small-scale acrylic painting with vinyl on the wooden panel is more than a backdrop. Sticking the randomly cut reflective vinyl surface with black and brownish red simulated the burnt marks, linking to the burning of laurel leaves in my story. The painting functions as a mirror, too, when a viewer stands before the panel, fragments of their reflection combining with the sculptural imagery born of fire. Thus, the viewers become Apollo for a moment, seeing themselves chasing the reflective glint, Daphne, or perhaps become Daphne, seeing their body part reflected as if turning into part of the tree. This interactive reflection is key to blurring the line between myth and contemporary experience. It completes the circuit of the story. Just as I wove myself as the storyteller into an ancient myth, now the audiences weave themselves into the story’s structure through their live reflection. The reflective vinyl also has a temporal effect. As lighting or the viewer’s position shifts, new aspects are created, echoing the layered temporal perspectives the work addresses. The wooden panel substrate references the arboreal theme, adding another layer of material resonance between content and form.

Throughout this process, I remained critically aware of the theories guiding my decisions. Haraway’s tentacular thinking was a constant companion concept. Whenever I combined media or symbol, I saw it as extending a tentacle across areas, from literature to smell, or from an ancient myth to a contemporary audience’s personal reflection. The final installation is meant to be approached not as a linear narrative to ‘read’ but as a network or ecosystem of elements to explore. In this way, it mirrors the tentacular interconnected structure of myth itself, that full of cross-references, multiple versions, and sensory details that connect across cultures. Bennett’s ‘Thing-power’ sharpened my attentiveness to each material’s expressive potential as well. Rather than treating the osmanthus flowers or vinyl purely as carriers of meaning, I impose, I allow their intrinsic qualities of scent and shine to dialogue with the narrative. This open, material-led method often led to surprises. For example, when I discovered that the aroma of the flowers grew stronger under the space’s warmth and gathered people, activating in the original place. It was as if the work itself breathed once installed, an embodiment of Bennett’s idea that nonhuman matter has its own vitality and agency. In addition, it speaks to Burrows and O’Sullivan’s concept of mythopoesis, which emphasises how creative behaviour can reveal and activate the power that transcends individual consciousness. Art or fiction becomes a channel to open and release inner potential, thereby promoting the birth of new subjectivity and social forms. This idea contributes to my research by creating new subjectivities through fictional narratives and new future communities for ‘the people to come’, providing deep conceptual grounding to my practice (Burrows and O’Sullivan, 2019, p.16).

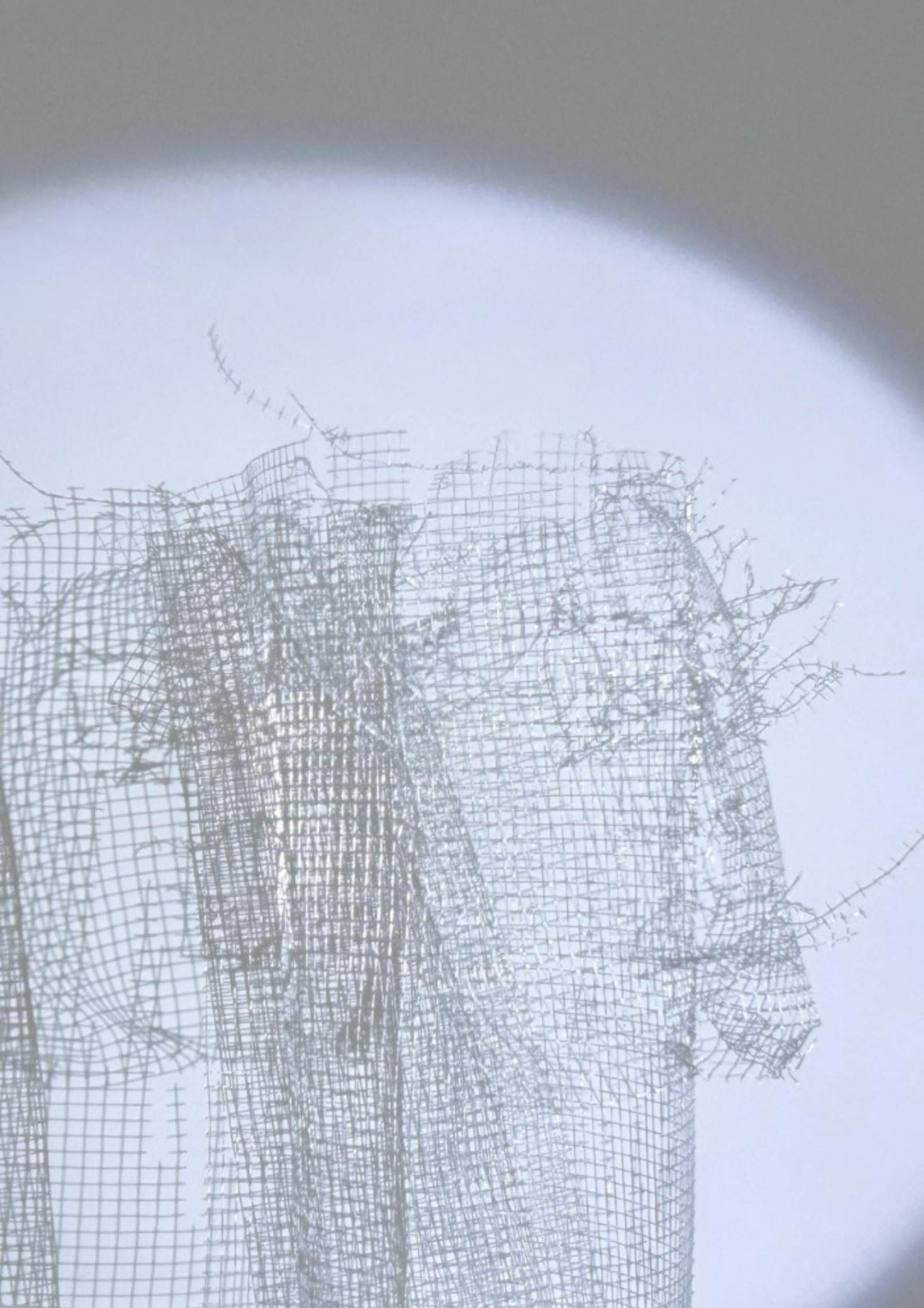

Audiences are not just observers, but co-creators summoned by the space in the intersection of senses and consciousness, where myths are reborn. Composed of three works, the whole installation explores how the audience’s interaction and spatial immersion jointly construct the ‘living’ field of the work, causing a shift in individual perception and thinking. From the small-scale sculptural painting on the wall to the hanging human-tree-mask-like sculpture, and to the large-scale interactive installation, audiences are gradually guided into deeper sensory involvement and conscious participation as the complexity and sensory experience of the works gradually increase. Different materials (wooden panel, reflective vinyl, acrylic, plaster, clay, wire, dried osmanthus, tree bark, Suzhou round silk fan, incense pearl) are interwoven to form an immersive environment, integrating visual, tactile, olfactory, and auditory senses for a holistic understanding and connection of the ecological and spiritual world.

When audiences approach the painting, the vinyl reflects a partial image of their body, prompting an interactive call for bringing identity into Apollo or Daphne, as mentioned earlier. Their self-images are fragmented and overlapped with mythology, breaking the passive viewing state, and actively re-examining their body and conscious boundaries. From this, the fusion of mythology and the present is initiated.

The original shape of the middle hanging sculpture, which derived from the tree in the place of Mother Shipton’s Cave, forms a new narrative space, crossing geographical and cultural boundaries. Perhaps influenced by the whispers from the wind blowing in, the slight swaying of the sculpture tempts the audience to come closer and into it. When the audience stands behind the sculpture and treats the sculpture as their own ‘mask’, their body and the sculpture merge into one. The participation activated the narrative potential of the work. Experiencing temporarily transforming themselves into a tree, the flow of consciousness and the actions of the body together constitute the ‘living’ field. This interaction lets the audience become a part of the work’s metamorphosis.

Attracted by the dried osmanthus aroma, the richer osmanthus smell from the incense pearls in the last installation invites the audience to walk around the work, finding a suitable height to smell, accompanied by the sway and sound of the hanging fans caused by the wind. As a catalyst for emotions and consciousness, the aroma brings the audience into a state of tranquillity and meditation, reconnecting their consciousness with laurel or osmanthus in the mythological narratives. The physical actions and perceptual reactions of the audience directly shape the scene of the work's existence, blending narrative with personal memory to form a constantly regenerating mythological experience.

The experience, emotions, memories, and consciousness transformation of the audience in interaction constitute a part of the meaning generation of the whole installation itself. The audience's perceived interaction is not only a response to the work, but also a co-creation of new narrative time, space, and individual experiences with the work, transforming the installation into a continuously changing mythological narrative field responding to current ecological and existential concerns.

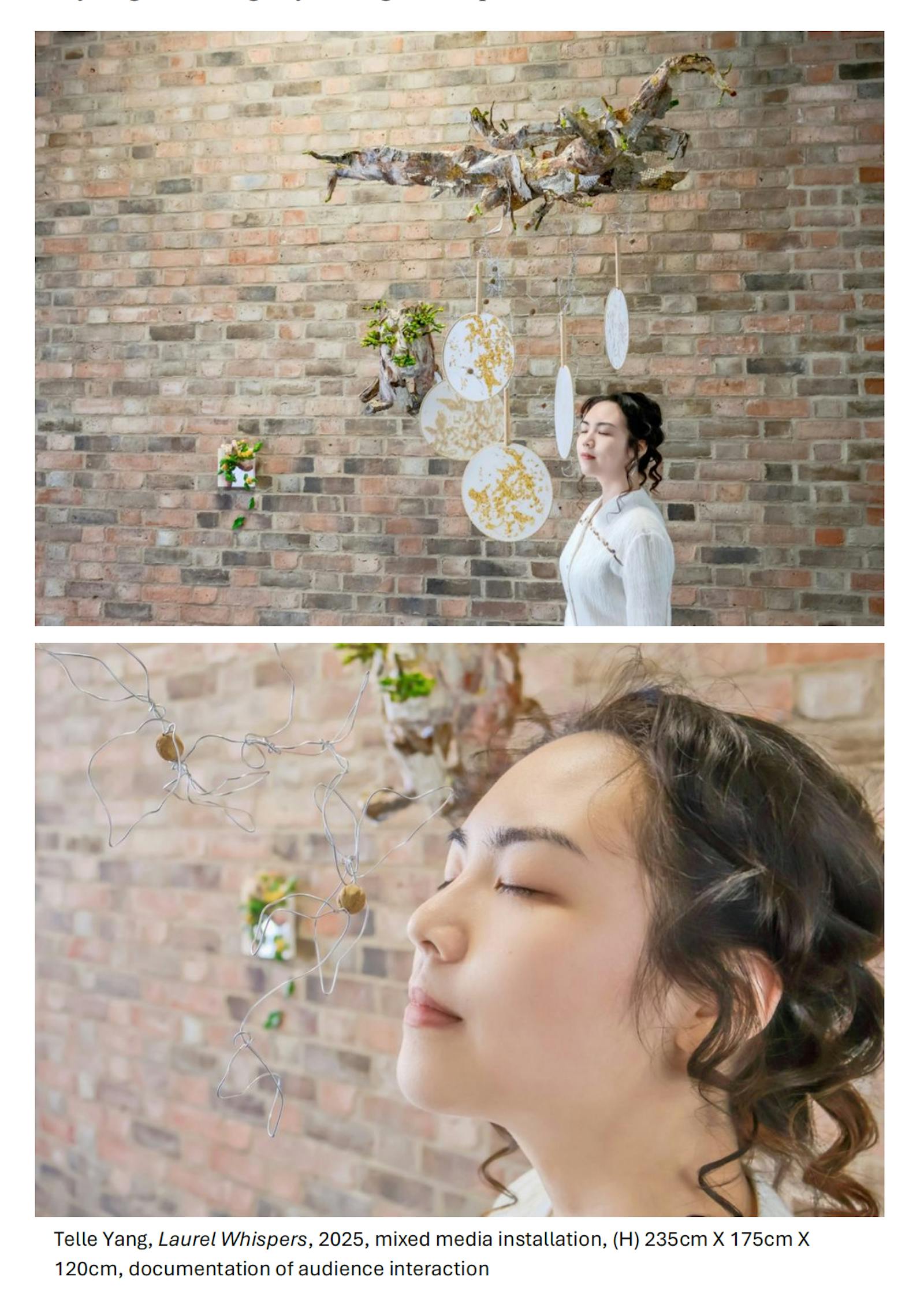

Telle Yang, Laurel Whispers, 2025, multi-sensory mixed media installation, (H) 235cm X 225cm X 150cm, (air-dry clay, acrylic, vinyl, dried osmanthus, wooden panel, wire, plaster, tree bark bit, Suzhou round silk fan, incense pearl)

Documentation of audience interaction

Telle Yang, Laurel Whispers I, 2025, acrylic, air-dry clay, vinyl and dried osmanthus on wooden panel, 32cm x 19cm × 7cm

Telle Yang, Laurel Whispers Ⅱ, 2025, wire, plaster, acrylic, air-dry clay, tree bark bit, vinyl, dried osmanthus, incense pearl, 50cm × 35cm × 40cm

Close-up documentation

Documentation of audience interaction

Telle Yang, Laurel Whispers Ⅲ, 2025, wire, plaster, acrylic, air-dry clay, tree bark bit, dried osmanthus, Suzhou round silk fan, incense pearl, 117cm × 61cm × 104cm

Close-up documentation

Close-up documentation

Close-up documentation