Robin Kirsten

Museum of Infinite Relations: artist's spaces, worlds and models of the universe

Summary

L’Atelier Brancusi, Paris, can be used as a model to configure a Museum of Infinite Relations. This hypothesis forms the foundation for a study of the systems, processes, rationale and methods used to produce a physical museum collection – a theoretical and material formation of the Museum of Infinite Relations.

Additional info

This research employs the paradigm of the monad, which is read through various proponents of the form, predominantly Pythagoras, Leibniz, and Beckett. It also considers the artists’ spaces of John Latham’s Flat Time HO, Helen Martins’ Owl House and Ferdinand Cheval’s Le Palais Idéal, alongside the concept of worlds, and models of the universe. By integrating the references, critiques and perspectives generated from the study, it binds them together into a way of thinking.

Research into the monad as a multi-functional device, apparatus, logic and lens is done through practice. Artworks produced during the research are brought together into the collection of the Museum of Infinite Relations, articulating a self-referential museum that generates itself through the creation of its collection. The questions of: what is a Museum of Infinite Relations, what is an infinite relation, and how does one develop that into museum, are approached through the methodology of applying the logic(s) of the monad and its associated representations and iterations, to trace the emergence of the Museum of Infinite Relations.

Connections are formed across multiple categories, such as ‘living sculptures’, Cosmism, retail display, studio performance and the idea of ‘event’, to mark out a terrain of concerns. This thesis mobilises the monad as a building block to sustain the argument for the development of the initial hypothesis into a working system. By predominantly locating the questions of this part-meditation, and part-critique, in L’Atelier Brancusi, this thesis develops an overview to support the reconfiguration of that site, into a model for expanding the paradigm of the monad as a methodological and conceptual structure.

The impact of this research considers how knowledge generated from an interpretation of what can be said is operational in artists’ spaces, which have been transformed into museological spaces, can be transferred. This is tested through a collaborative project that draws on multiple strands encountered during the research. In this sense, it can be said that the museological space breaks out from the confines of the static building and institutional boundaries, and becomes embodied in the lived experience of a collaborative theatrical performance.

STUDIES FOR A MUSEUM

Studies for a Museum was presented at Object | Image | Text, Cape Town (2020), and consisted of the works below.

Study for a Museum of Opening Doors

This sculptural installation was developed out of an earlier piece with the same title, of an architect’s drawing of the house my family built, which I worked over using a compass and black ink. In that drawing, which is written about in the writing sample, I used a compass for the first time to locate multiple symbols of the monad on top of the drawing. The point of the compass was positioned at corners and junctions, with the arc of the circle drawn within and around the open spaces indicated in the plan.

I was trying to visualise a building where entering and exiting are experienced simultaneously, so that the body is travelling through doors but never going anywhere. This experience of liminality might have been achieved with revolving doors, or doors that could swing 360 degrees on an axis.

As a space of transition between one world and the other, the sculptural installation presented only doors permanently fixed together at their hinges and shaped into a mini labyrinth, or passage. Doors were treated in various ways, with some remaining solid, and others half or fully exposing both spaces on either side of the door.

Whenever a doors internal panelling was solid, the one side was filled with black back-painted glass, and the reverse side inserted with fabric covered panelling. This black glass is naturally reflective, and had the effect of multiplying what was reflected, sometimes infinitely, especially when two reflective surfaces faced each other.

Each doors style and form references a different type of space, building or room. This can be institutional, as in on office door, private, as in a bedroom, or a door that leads you in or out of a building, like back doors or front doors. They also refer to different historical periods through their style and materiality of different types of wood and surface treatment, with some strongly indicative of specific eras, like the 1940s, 1950s, 1970s, 1980s etc.

Along with these historical references to style, production values and places of installation, is a deep memory encoded into the doors. These are traced in marks, dents, scratches and other residues of the passing of time, and exposure to years of use. Additionally, these are doors that can still be encountered in a range of buildings, and they are able to bring up memories of places I, or the viewer, might have previously been.

The viewer is able to walk through around the structure. In some places, the effect of the reflection is confusing, and it is uncertain if there are more doors, or additional glass panelling. In these areas, the labyrinthine quality emerges fully.

The point of making this work was to provide an experience of the transition between spaces, or worlds, that are both liminal. Given that the doors don’t lead anywhere individually, it’s not possible to go to the other side. The doors don’t function as doors. Instead they lead you through another space carved out by the static and fixed doors. This is the space of incoherent and unfamiliar effects.

Reading this work back into my research project, the multiplying of spaces through the use of reflective surfaces, and constructing a kind of building or potential dwelling from doors, with all its residual qualities, has become useful to expose another angle to my reading of Renzo Piano’s L’Atelier Brancusi.

Study for a Museum of Quantum Objects

In this room I presented three works, collectively brought together within the focus on quantum objects. I was interested in looking at quantum objects as I interpret the monad itself as having the characteristic of appearing in several places simultaneously. My interest lies outside of the larger body of research into quantum physics, as it is the poetic and artistic possibilities in thinking through the basic premise of an objects ability to not only exist everywhere at the same time, but also, it’s ability to appear to move itself across and into different locations, that is the starting point for these three works.

The idea of objects moving into different locations with seemingly free will, links back into Brancusi’s last decade, where objects were able to occupy different locations, although this was done with the force of Brancusi moving them himself. What if, I asked myself, the objects in L’Atelier Brancusi, were ‘switched on’ again, and were able to move themselves around? Where would they go, and what mobile groupings could they arrange themselves into?

This moving image work was created by filming a performance of myself pretending to be Brancusi, moving objects around in the studio into several groupings, and then cutting myself out of the footage, so that the objects appear to move by themselves. I appear in three consecutive clips as an object, the Artist in a Black Suit.

Each object was given a few set movements which related to its shape, for example, a low squared off table could ‘walk’ through its various sides, or a glass vase was able to bounce from one surface to another, acting like a vase. Where objects were stackable, they were allowed to reach as high as they could.

Study for a Museum of Multiple Vectors (in four parts)

In this room, I presented four glass display cabinets, each containing a variety of found and reworked objects collected from a range of outlets, or provided by other people. I also included an earlier painting, and a wall-hung desk drawer. My intention with this work is to continue it is an ongoing piece, but in this case, I only presented four cabinets out of possibly endless quantity.

The windows of the room were replaced with mirrored glass sheets, so that the room itself resembled a cabinet. I wanted to present the idea that the cabinets are in a cabinet, and that the viewer is also in a cabinet containing other cabinets. This decision, of placing the one in the other, is a representation of an idea proposed in the holographic paradigm, that the whole is accessible from the part.

In this installation this idea is communicated, or suggested visually and experientially, that the cabinets in the room are in a cabinet which is the room, outside of which is a larger cabinet called world. This also touches on the way that infinity can be found in both the macro and micro, which means that infinity can be located in all directions. And if it can be found in all directions, then it can also be found in the here and now. By multiplying the surfaces to reflect each other, I hoped to make these qualities or characteristics present.

The reference to multiple vectors in title of this work, was used to indicate four ways into this collection: a) that the objects on display existed in different contexts prior to my acquisition, b) that they have a line of trajectory that will continue as long as they do, c) that amongst and within them are qualities, forms, and references, which might be interchangeable, shared or overlapping, and d) that they can be swapped around in the cabinets without changing the meaning of the work. This last indication again refers back to Constantin Brancusi’s work in his last decade, of moving objects around into different display arrangements, his ‘groupes mobile’.

In Study for a Museum of Multiple Vectors, I have worked to retrace Brancusi’s method of moving objects around until they rest in a satisfying position. There is no overriding logic as to which objects remain in what position, although certain obstructions have an influence on determining what goes where. For example, the weight or size of an object, restrictions in accessing the internal space of a cabinet, and the desire to balance out the aesthetics so that focus points are spread across all four cabinets.

Whilst the method for constructing these cabinets is a retracing of Brancusi’s moves, the cabinets themselves are a close iteration of how his studio is now presented. Like the cabinets in my work, Renzo Piano’s L’Atelier Brancusi can be viewed as a large glass display cabinet, containing hundreds of objects with their own lines of flight, or multiple vectors. Brancusi’s tools, furniture, equipment, sculptures, images et al, have not only been moved by him in his own studio, but the studio itself has been moved three times since its original relocation.

Various mannequin parts are placed in my four cabinets, with each cabinet containing at least one part. Treated in different ways by changing their surfaces, or casting them in plaster, each part does the work of signifying the individuality of each cabinet, and to narrate each cabinet.

The choice to bring in objects that reference the body, was to highlight Nikolai Federov’s idea about the role of the future museum, and to activate each cabinet with a potential future life. In essence, his proposal was that objects, or at the smallest level, dust, should be used to recreate the lives of the people who owned the objects, so that they too could benefit from the future emancipation from death. An idea he thought should be the role of curators, who would use the craft and technologies of conservation, to eliminate death and overcome nature. Emancipation, he believed, should be available to everyone who has ever lived, and not just those who are already alive or those who are to come.

In each of my cabinets the mannequin parts narrate an experience of being. These are a)

desire/want, b) interaction/exchange, c) brotherhood/love, and d) death/transformation. They are placed on the Cartesian Grid of the vertical and horizontal, so that they sit in the direction from where vectors can be measured, and where coordinates can be identified.

Nothing is Here

The title of the performance was generated during lockdown, and prior to developing the actions of the performers, the music, the scenes or any narrative possibilities. As we had nowhere to go, nothing to do, no one to see, Nothing is Here seemed like a fair overview of the prevailing conditions.

And the structure around which the entire piece was activated and motivated, Study for a Museum of Opening Doors, also suggested this title as relevant, as that work intended to elicit to experience of liminal space. A space of transition between two or more other worlds.

A call was made out for proposals for a season of new theatrical works, titled 2 Metres Apart: Making Theatre in the Age of Corona. And it was vital that any works proposed had to comply with government regulations regarding social distancing between audience members and the cast and crew. The structure of 10 doors at the centre of the stage seemed like a fitting method for representing several aspects of these regulations, such as the requirement to remain mostly indoors. And also, the measurements of the doors, which allowed me to calculate and represent 2 metres, both vertically and horizontally.

In the end, the distancing was only applied to the relation between the audience members themselves, and the edge of the stage, as the groups of cast members included, either lived together or were working together closely on other productions. Likewise, the theatrical director I worked with, I lived with, and the musical director naturally became close to us all during rehearsals, rendering his need for distancing, obsolete.

The two groups were a puppetry collective, Ukwanda Puppetry and Design Art Collective, who ordinarily make large scale puppets under the tutelage of the University of the Western Cape, and Handspring Puppet Company. The two dancers were drawn from Unmute Dance Company, whose members are of mixed disabilities. One of the dancers, Andile Vellem, is deaf, which directly influenced how we were going to create direction and choreography to a purely musical score, which we did with lighting cues, vibration (foot stomping), and direct prompting through touch and body signalling.

The musical director, Godfrey Johnson, and I, worked on composing a score, which could be metronomic but elastic, so that he could respond to the variations in the performance timing which was not set and also to adjust to Andile’s own sense of timing. The baseline of that composition referenced the music by Hada Benedito Mateo for Maya Deren’s silent dance-for-film work, Ritual in Transfigured Time (1946). Meredith Monk’s 1983 work, Turtle Dreams, suggested how we could develop a metronomic pace to the score. Our score, titled Deconstruction for Nothing in E-minor, was played on an out of tune piano, with its strings exposed to be plucked as part of the instrumentation.

Theatrical Director, Craig Leo, worked with me to translate and adapt the research references, artistic concepts, structure and logic, into the piece. Movement Director, Themba Mbuli, an associate of Unmute Dance Company, polished and refined the dancers own choreography which we generated through workshops prior to rehearsals.

Concepts and structural logic

The staging for this piece was developed out of the structure of L’Atelier Brancusi, with the audience placed on the ambulatory encircling the central stage. The original front facing stage of this theatre hall was removed and replaced with a centred series of wood panels, in the centre of which I placed the 10-door sculptural installation, Study for a Museum of Opening Doors. This structure divided the stage into three distinct areas, where different actions were performed simultaneously. The concept of the fourth wall, which in traditional theatre making is both the edge of the stage in line with the proscenium arch, as well as the idea of being unable to break into the audience to involve them in the action taking place on stage, now ringed our central stage to mimic the glass walls surrounding the three rooms that make up Brancusi’s studio space in the middle of Renzo Piano’s building housing it.

Instead of breaking through the fourth wall, as Bertolt Brecht tried to do in his Epic Theatre, we kept it in place to both enforce the bio security that social distancing enables, and to remain close to the reality of the glass walls separating the viewers and internal non-activity of L’Atelier Brancusi.

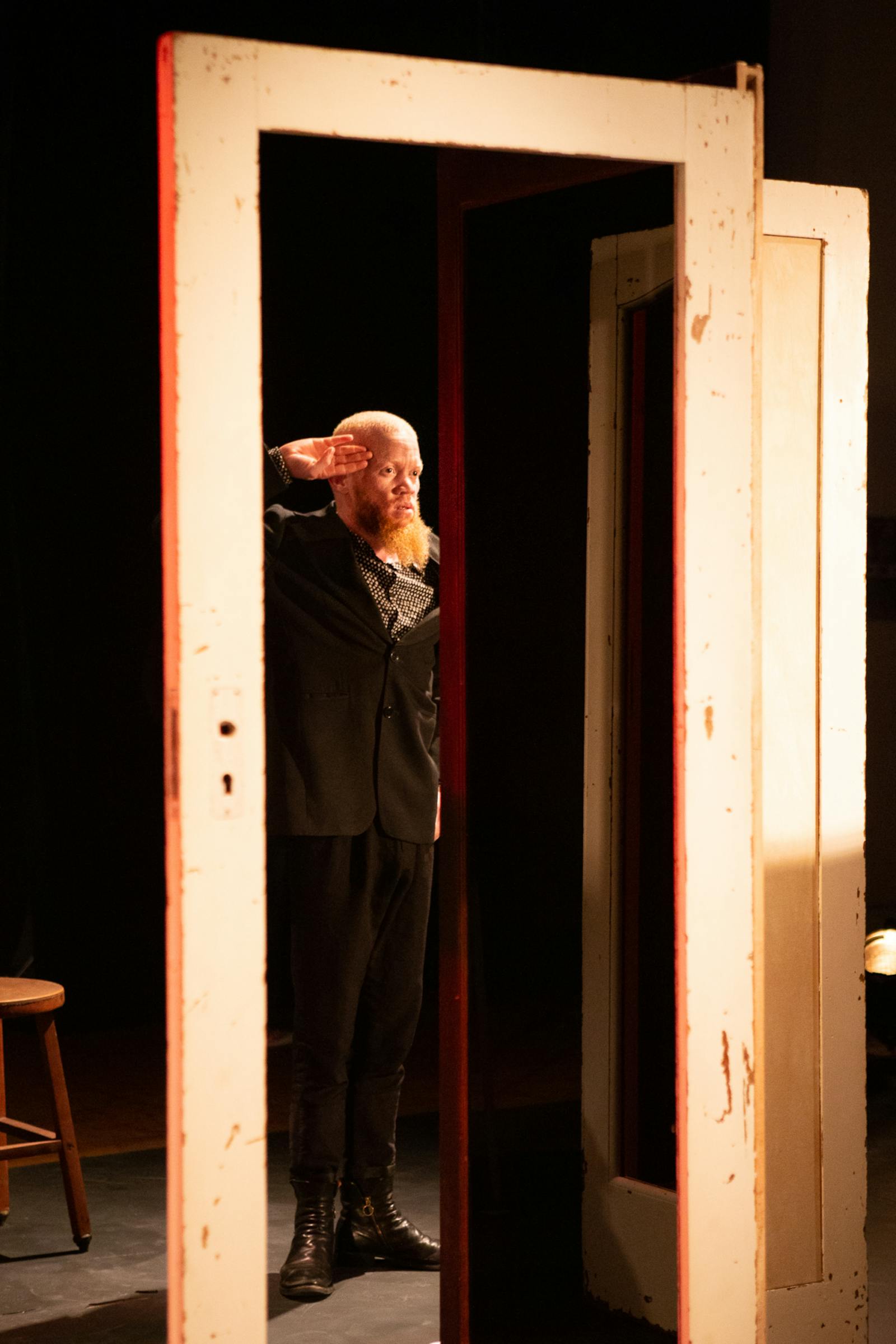

Artist in a Black Suit

This character of mine was placed throughout the performance on a stool with a metal pail on his head, played by Luyanda Nogodlwana. This informed the narrative of the work, which was that the entire piece was something he was imaging in his head whilst staring into the blackness of the void space symbolised by the dark interior of the pail. He was directed to respond the changes to the music, the closeness of performance action, and was also used by another character, The Woman and The Leg, to hold onto her mannequin leg sculpture, when she needed him to. Sometimes he looked at his watch that he could not see, as a statement on the absurdity of marking time in the timeless space of an infinite void.

The Woman and The Leg

Played by Siphokazi Mofu, this character interacted with furniture, objects, our Musical Director Godfrey Johnson, who was The Piano Man, and another character who had his leg caught in a pail, Puppet Man, with who she also danced a tango for three. I created a sculpture for her of stacked objects comprised of a black glitter sphere, on top of which was a mannequin leg, topped by a large polystyrene ball. This sculptural prop was given a handle so that she could operate it as a walking stick (a third leg), and a dancing sculpture for her tango.

Artistic Director: Robin Kirsten

Theatrical Director: Craig Leo

Musical Director: Godfrey Johnson

Movement Director: Themba Mbuli

Unmute Dance Company:

Andile Vellem

Siphenathi Mayekiso

Ukwanda Puppets and Design Art Collective:

Siphokazi Mofu

Luyanda Nogodlwana

Sipho Ngxola