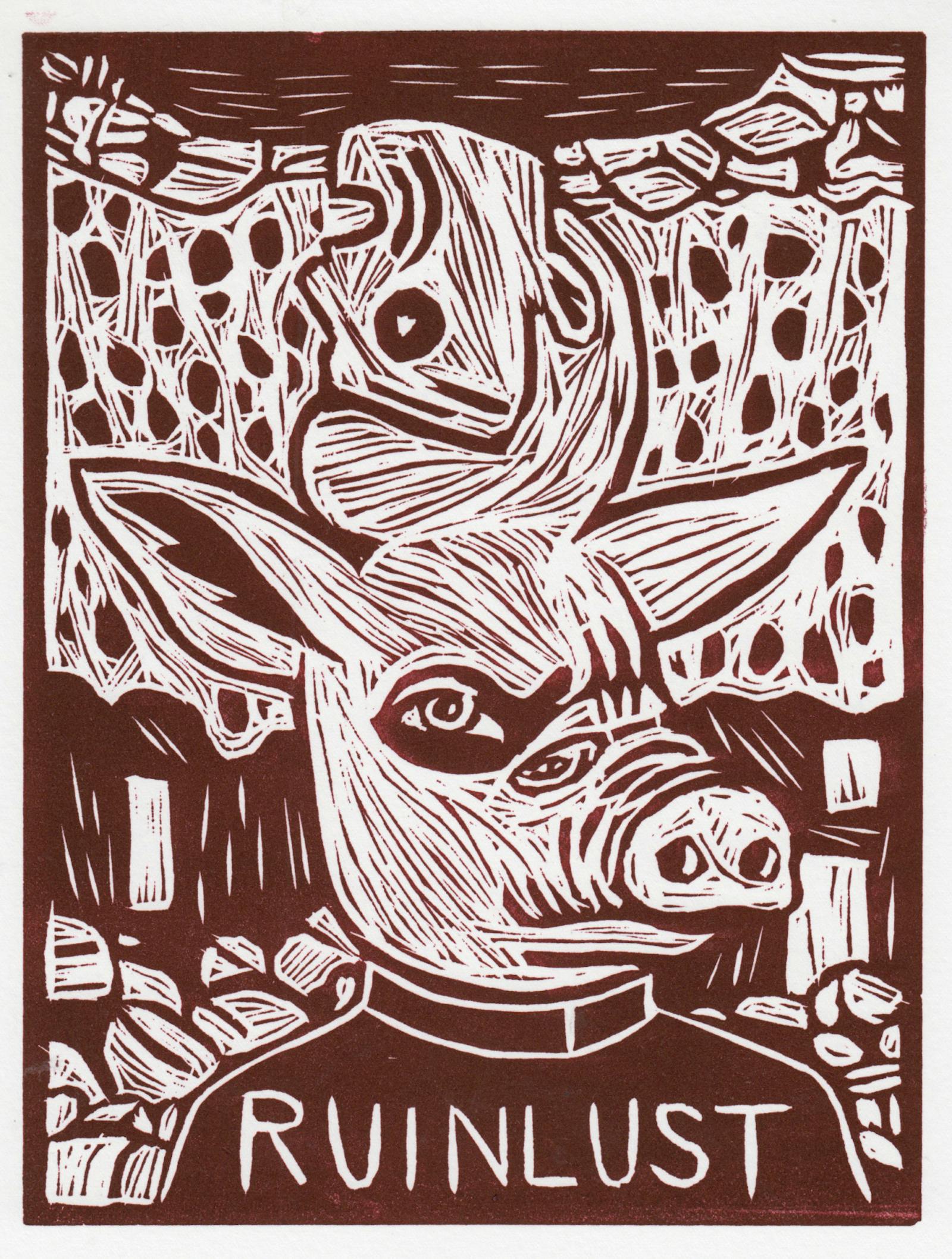

Hannah Brinkmann

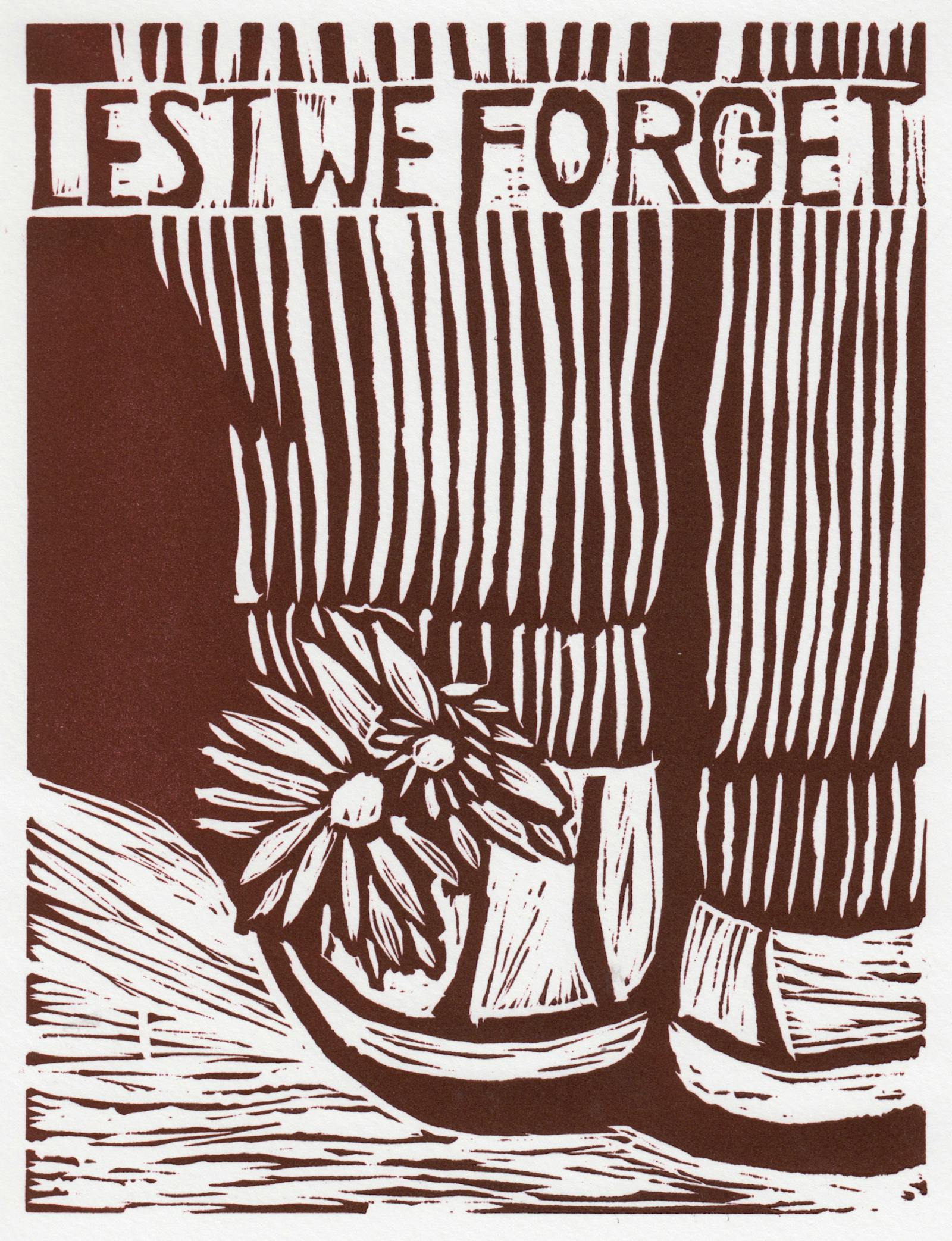

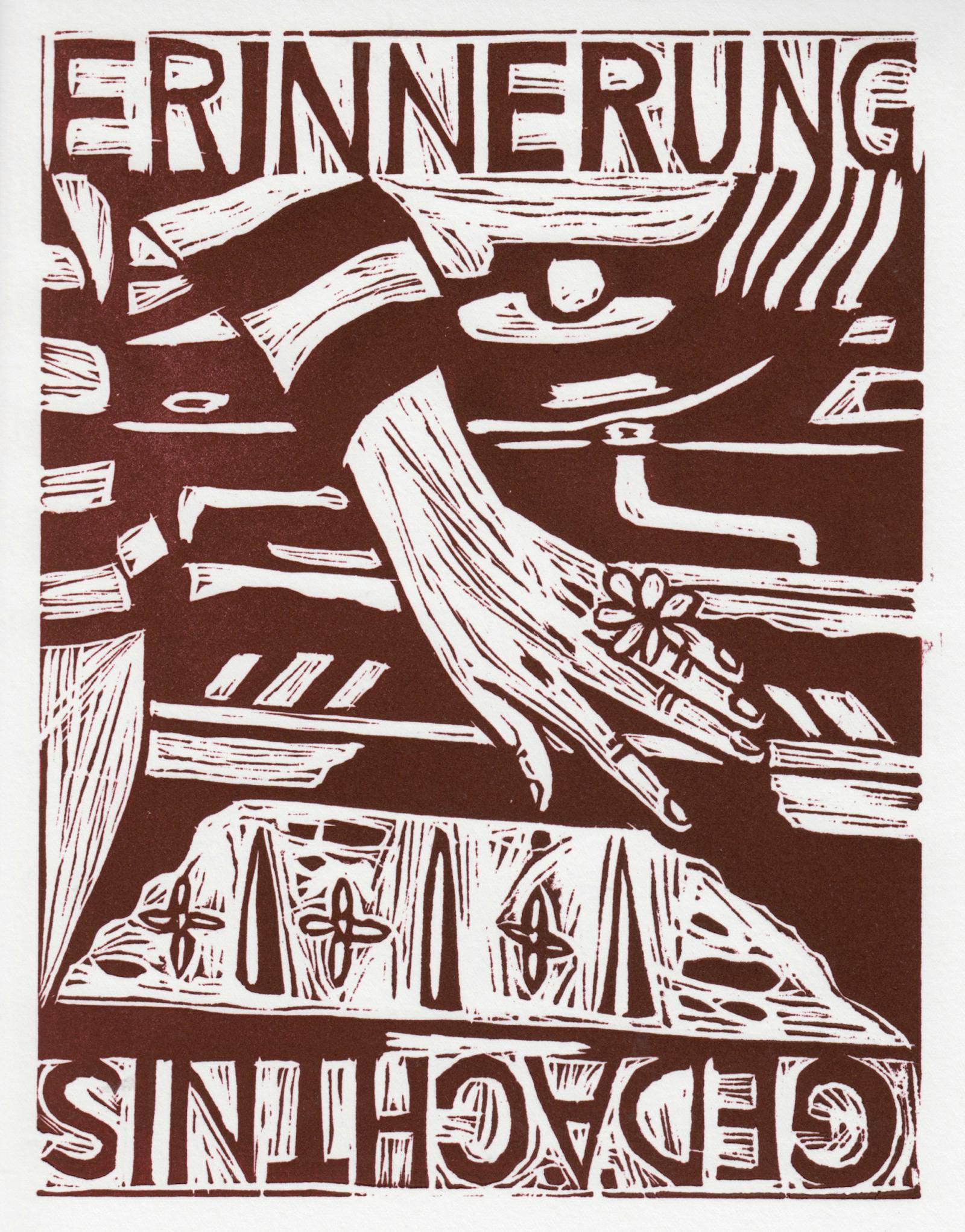

The past was sunk in cement

Summary

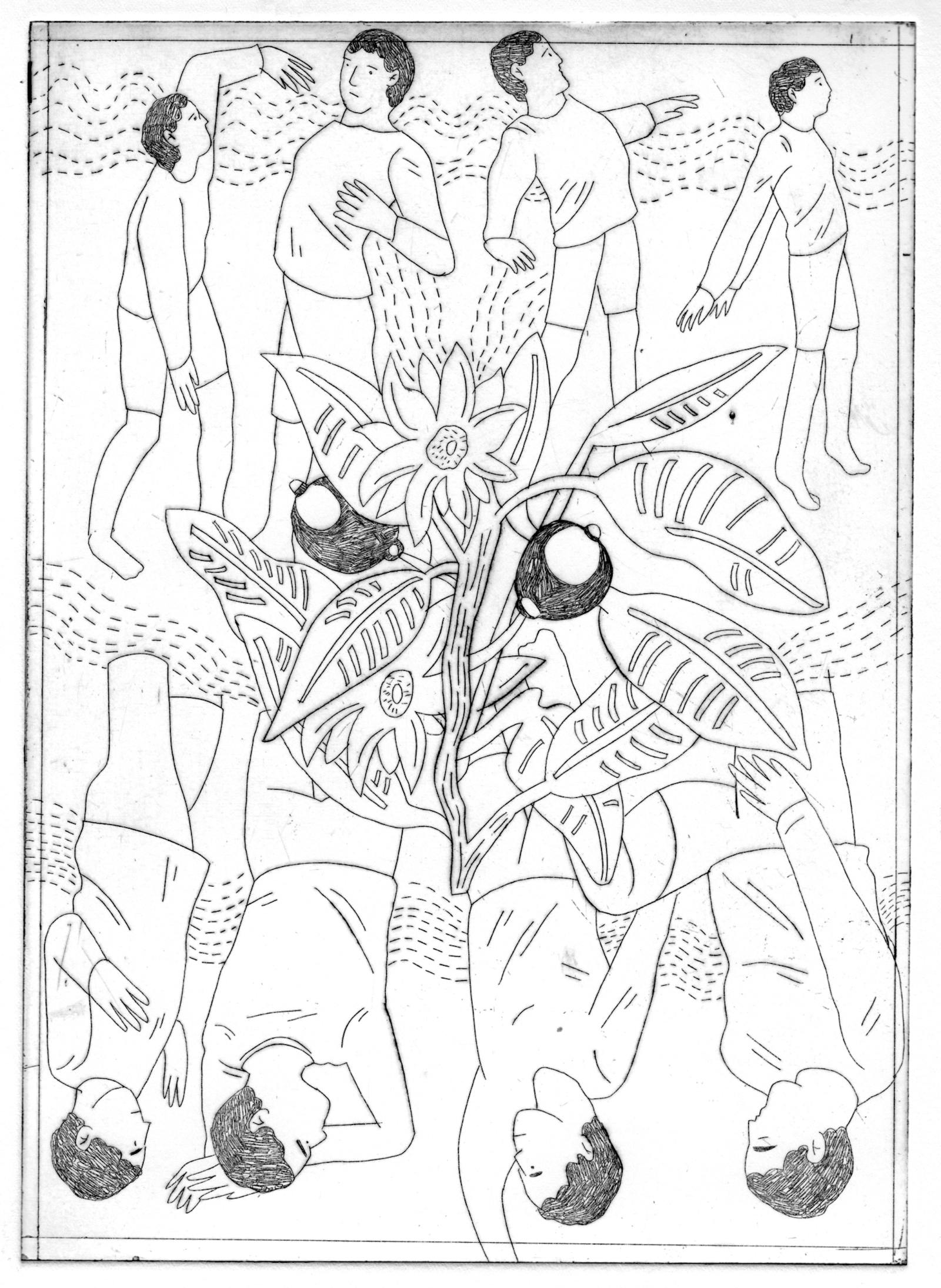

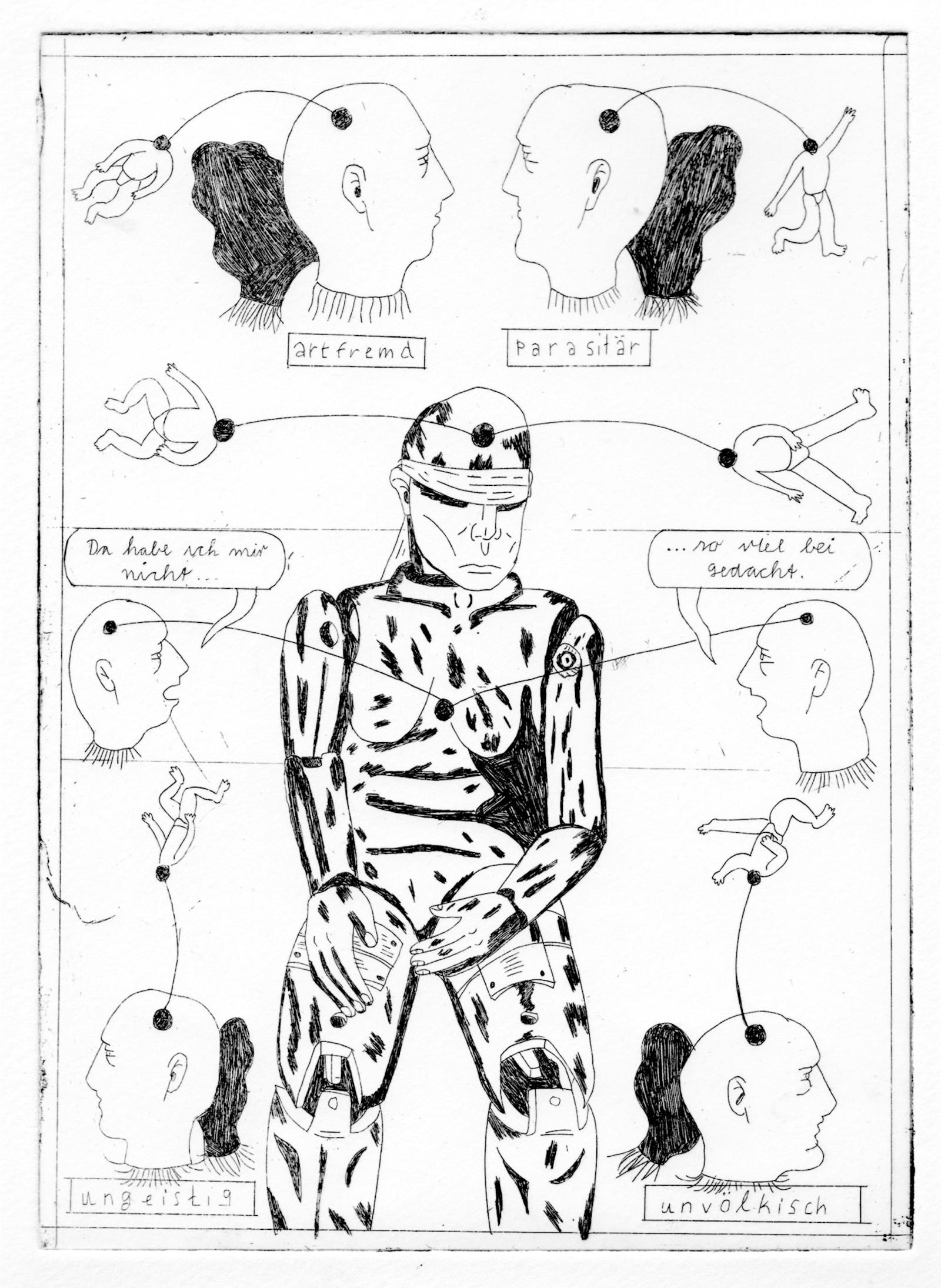

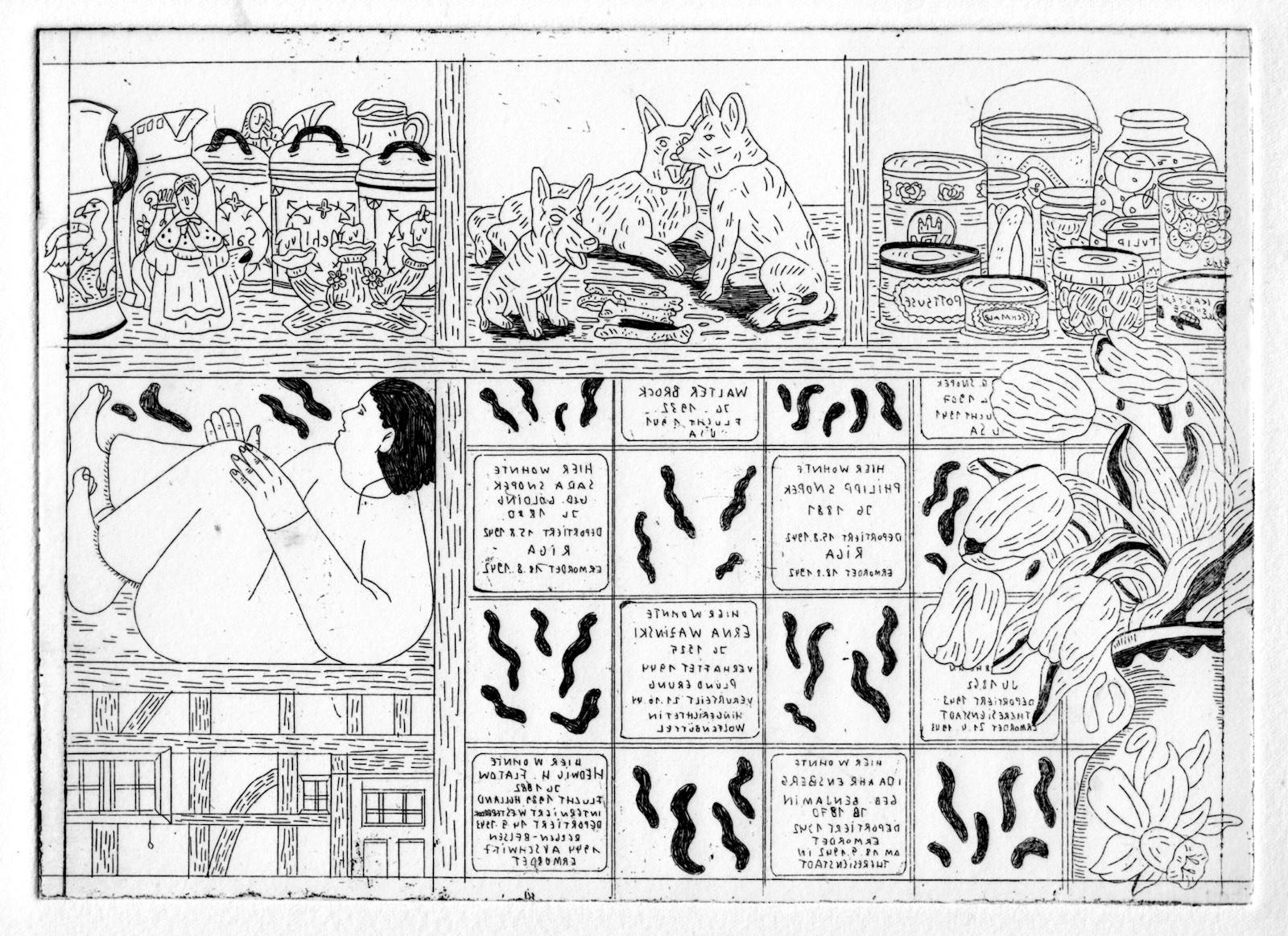

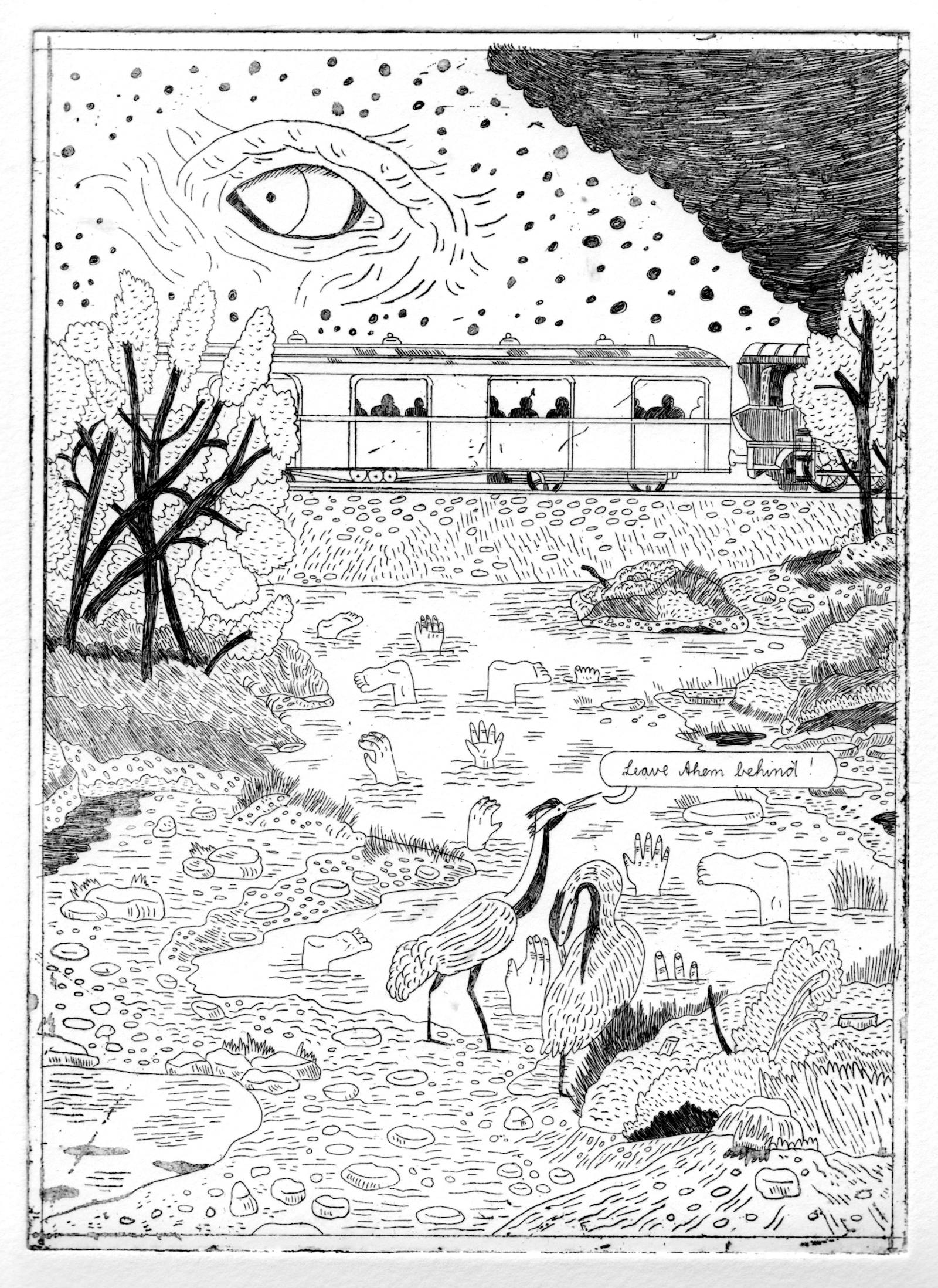

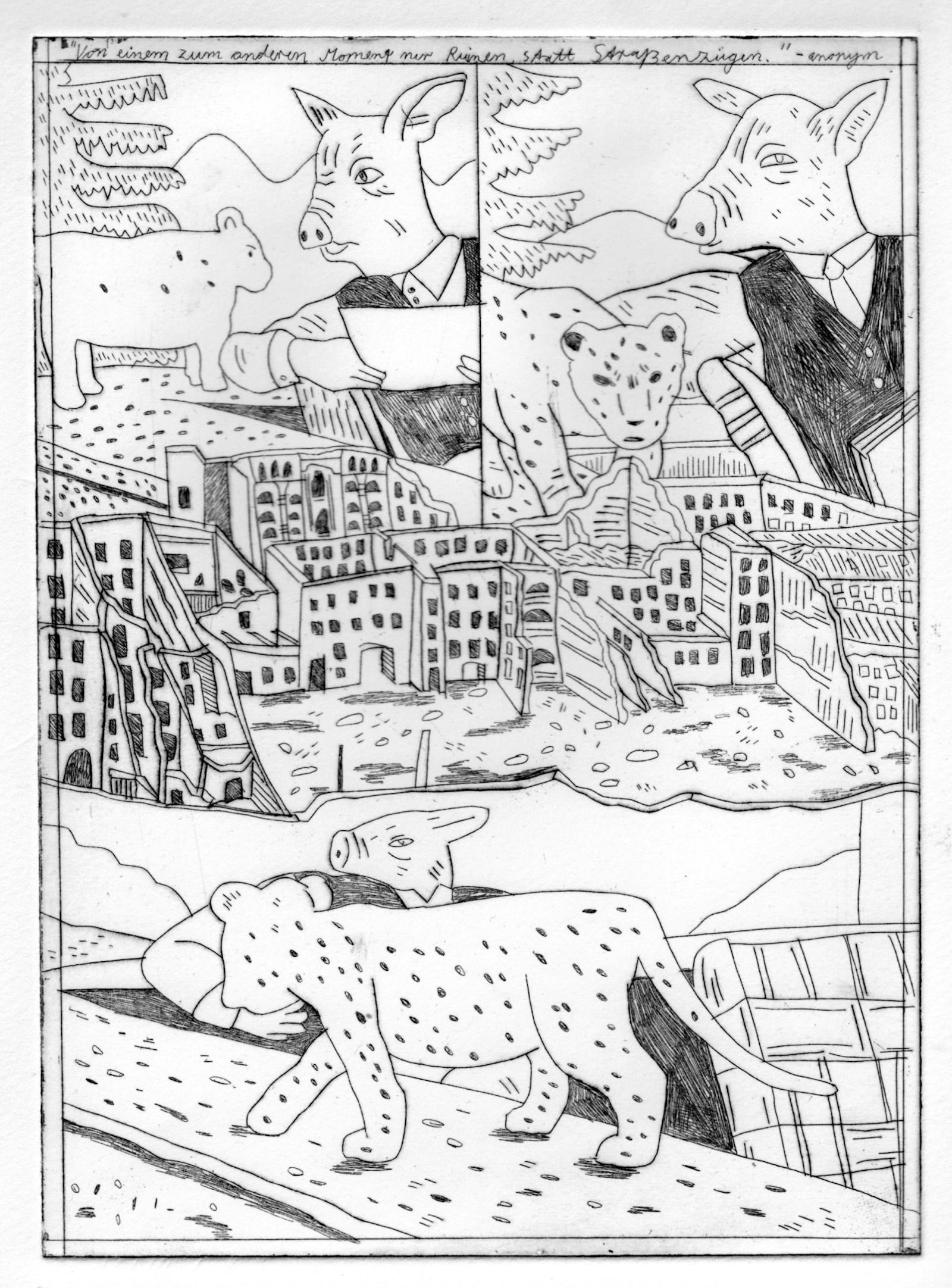

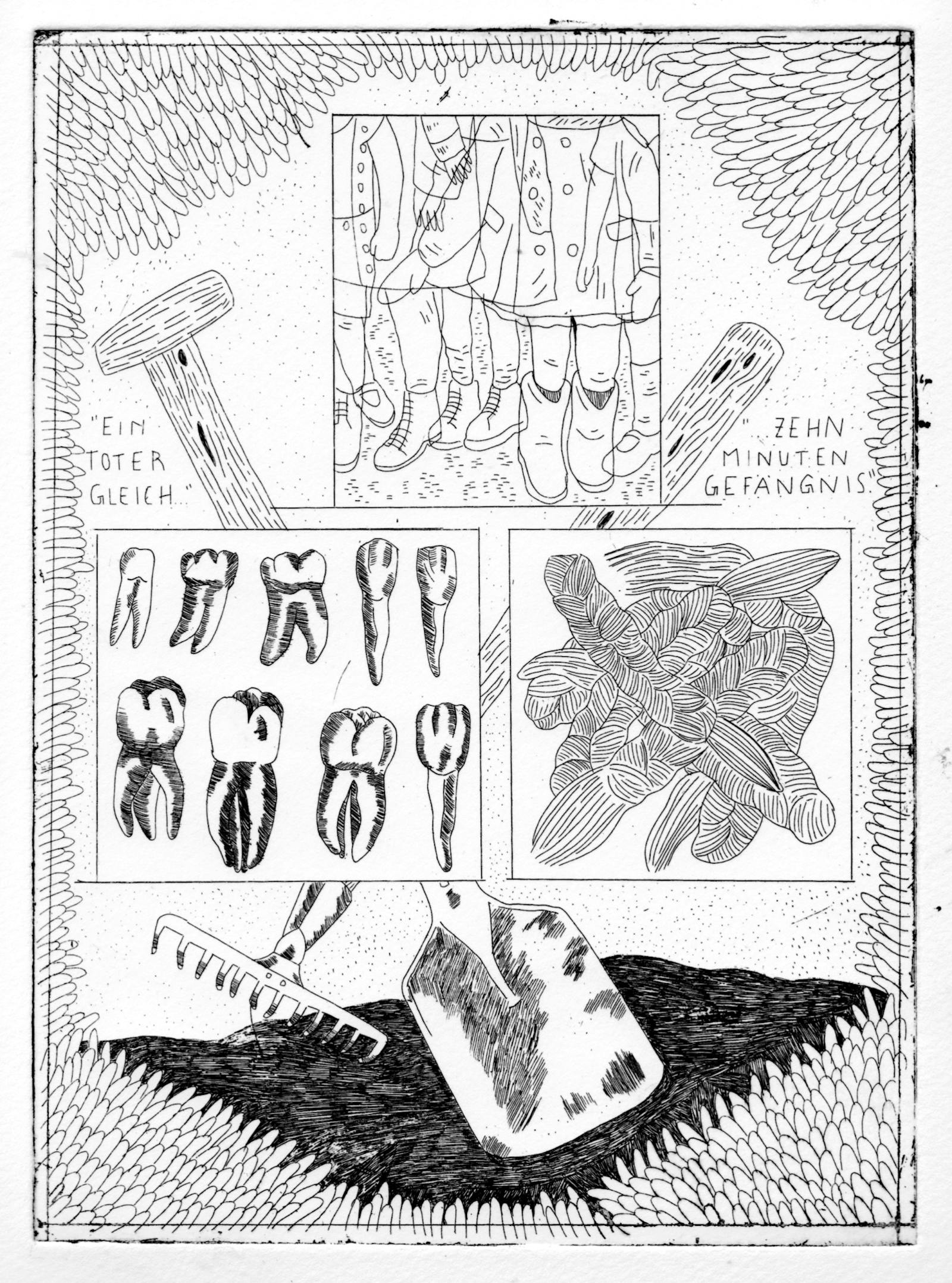

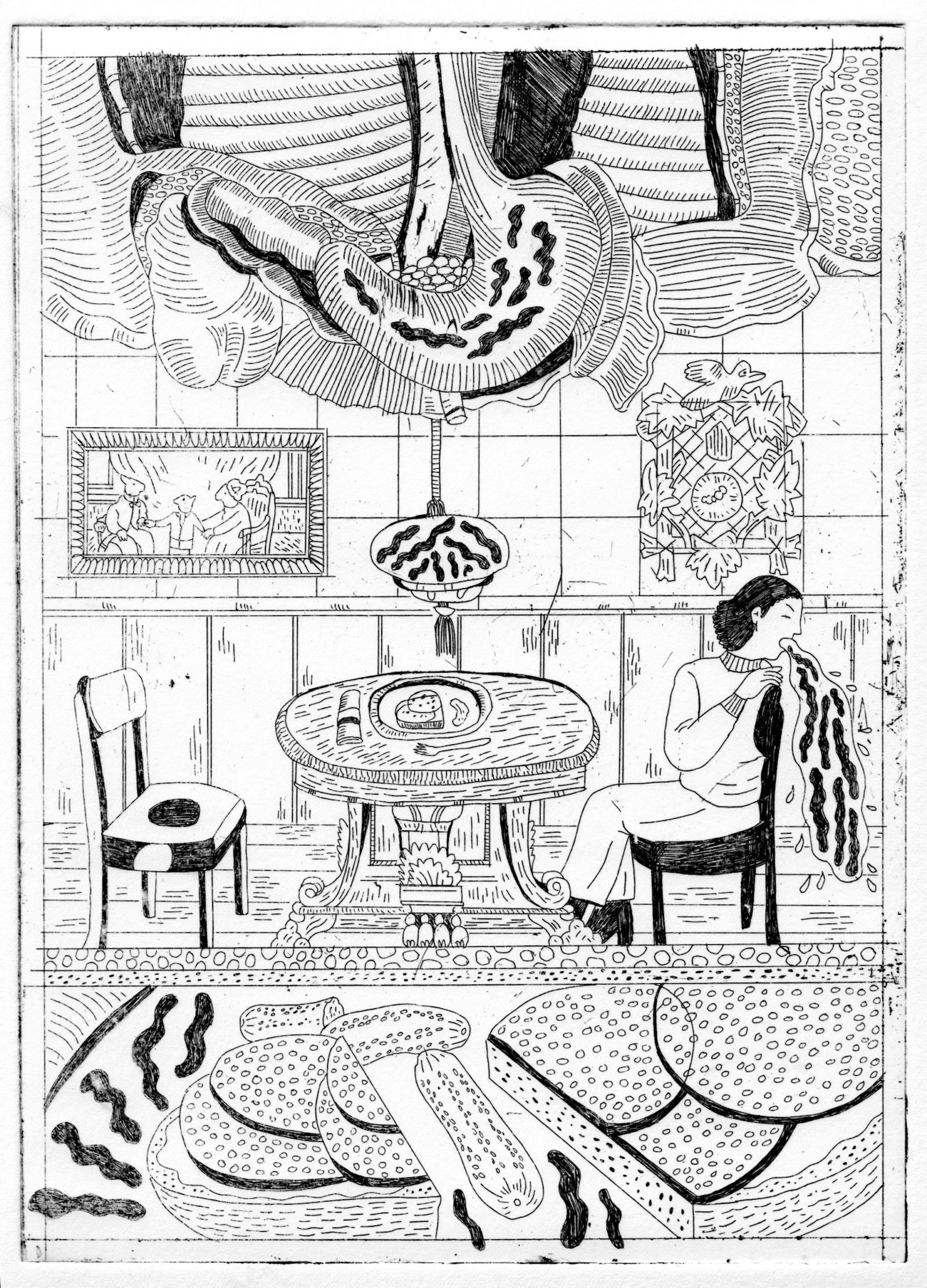

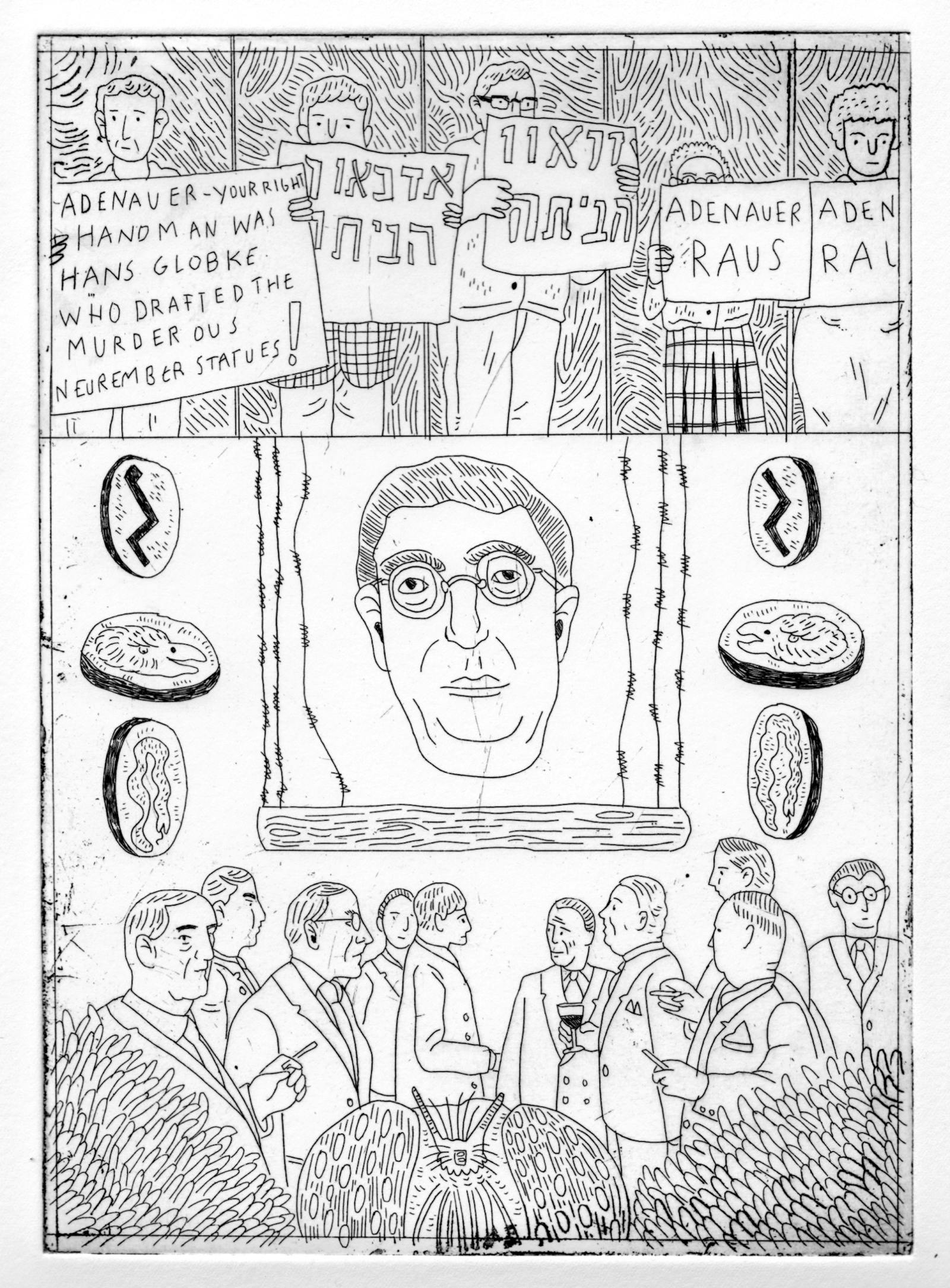

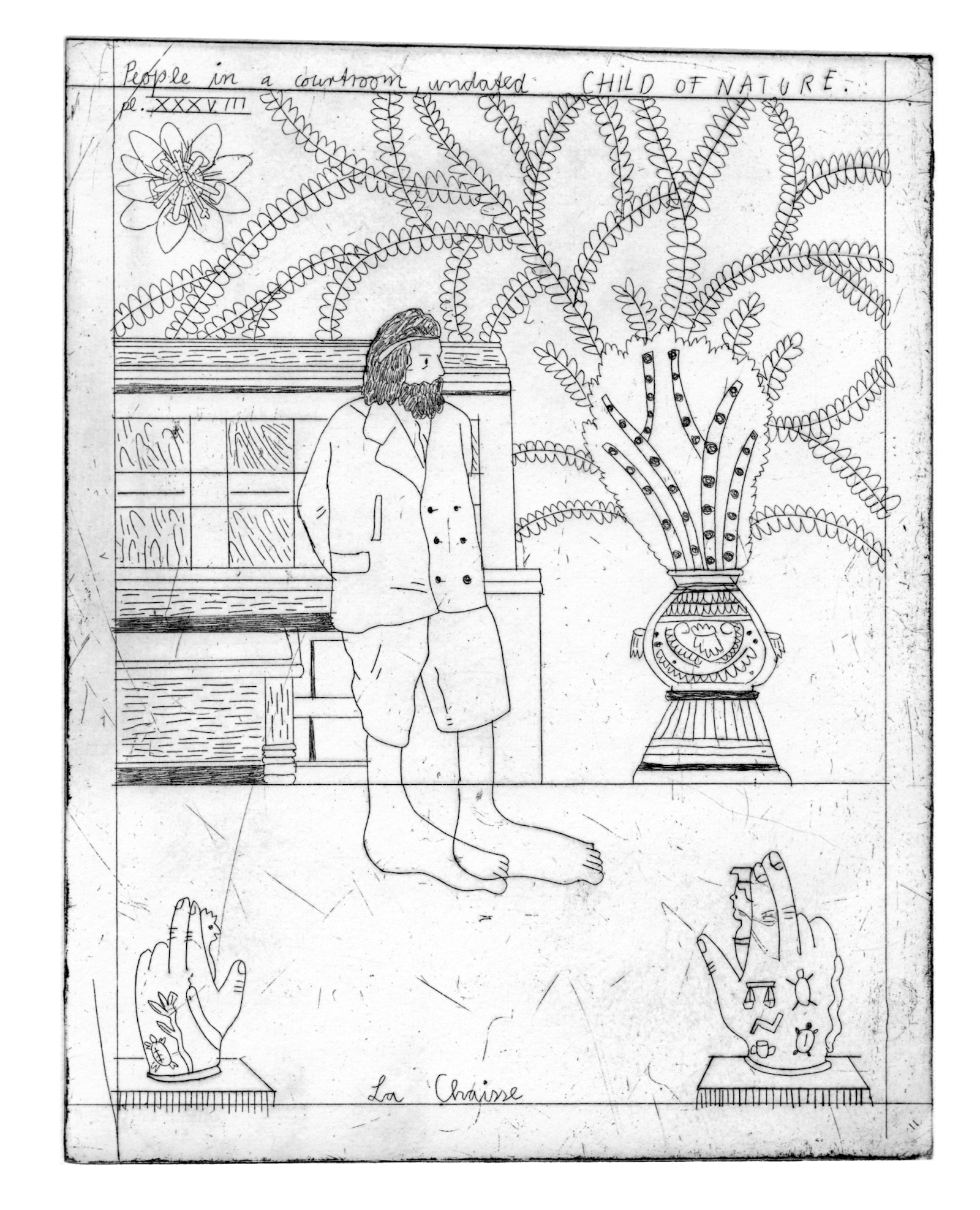

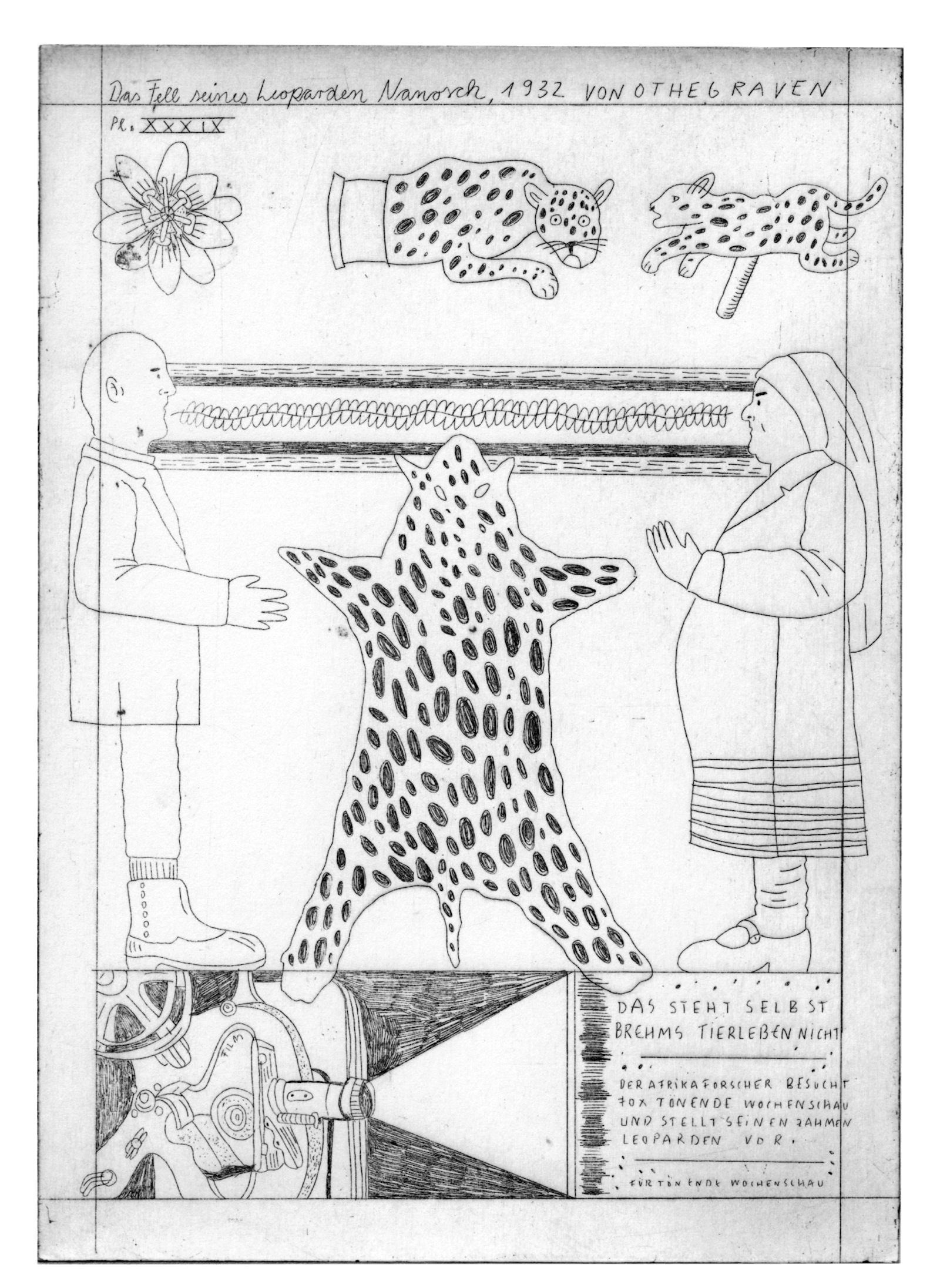

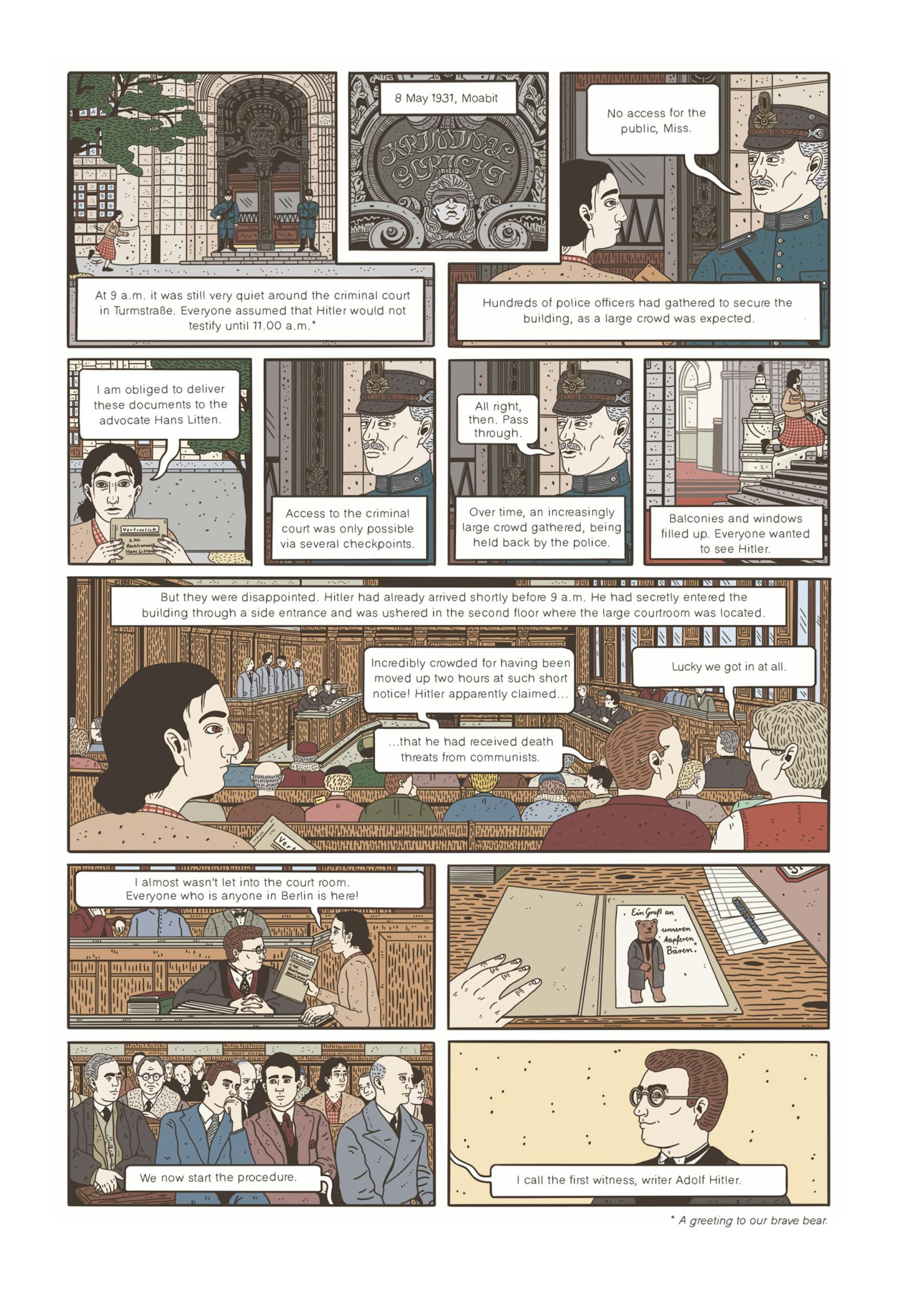

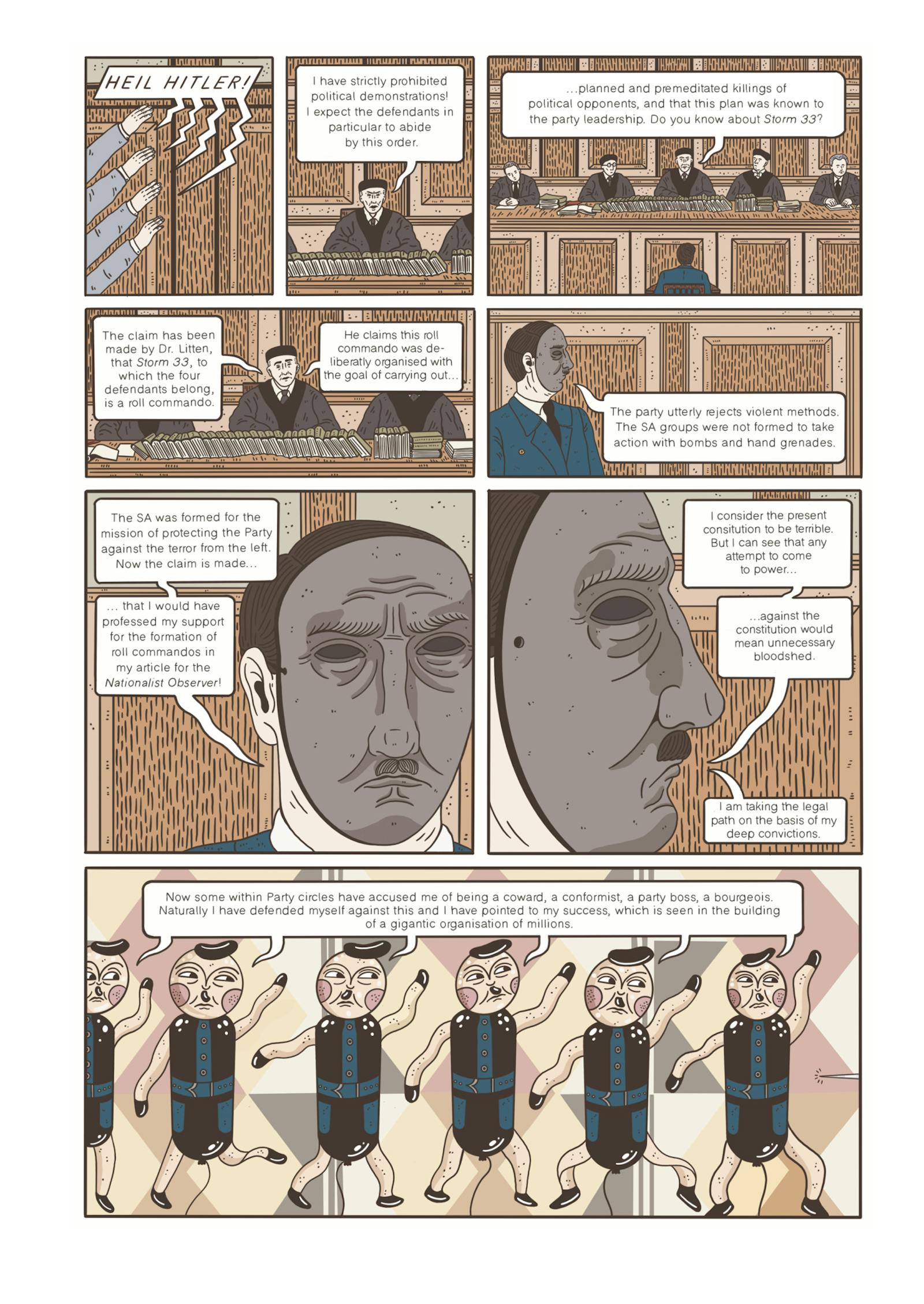

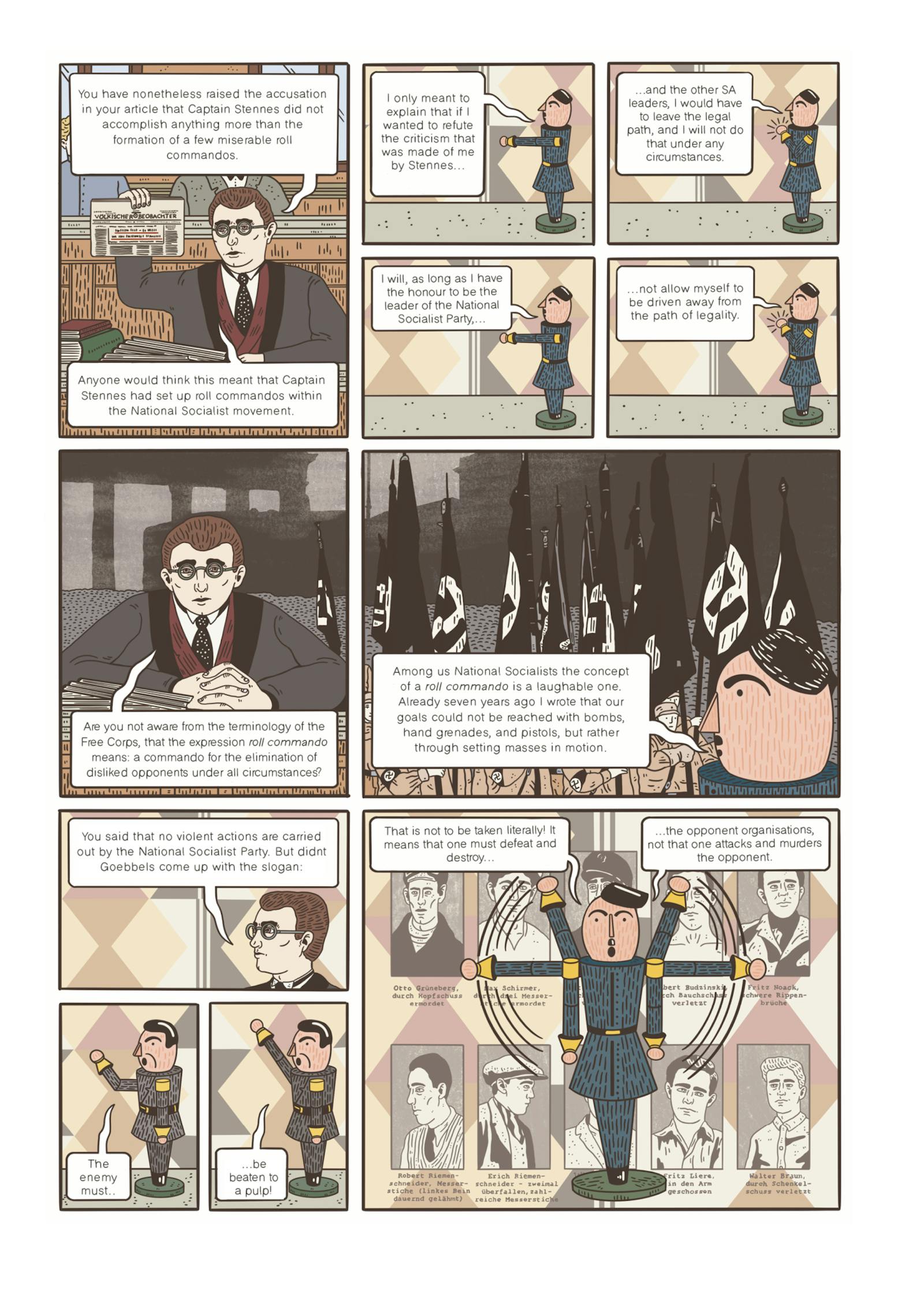

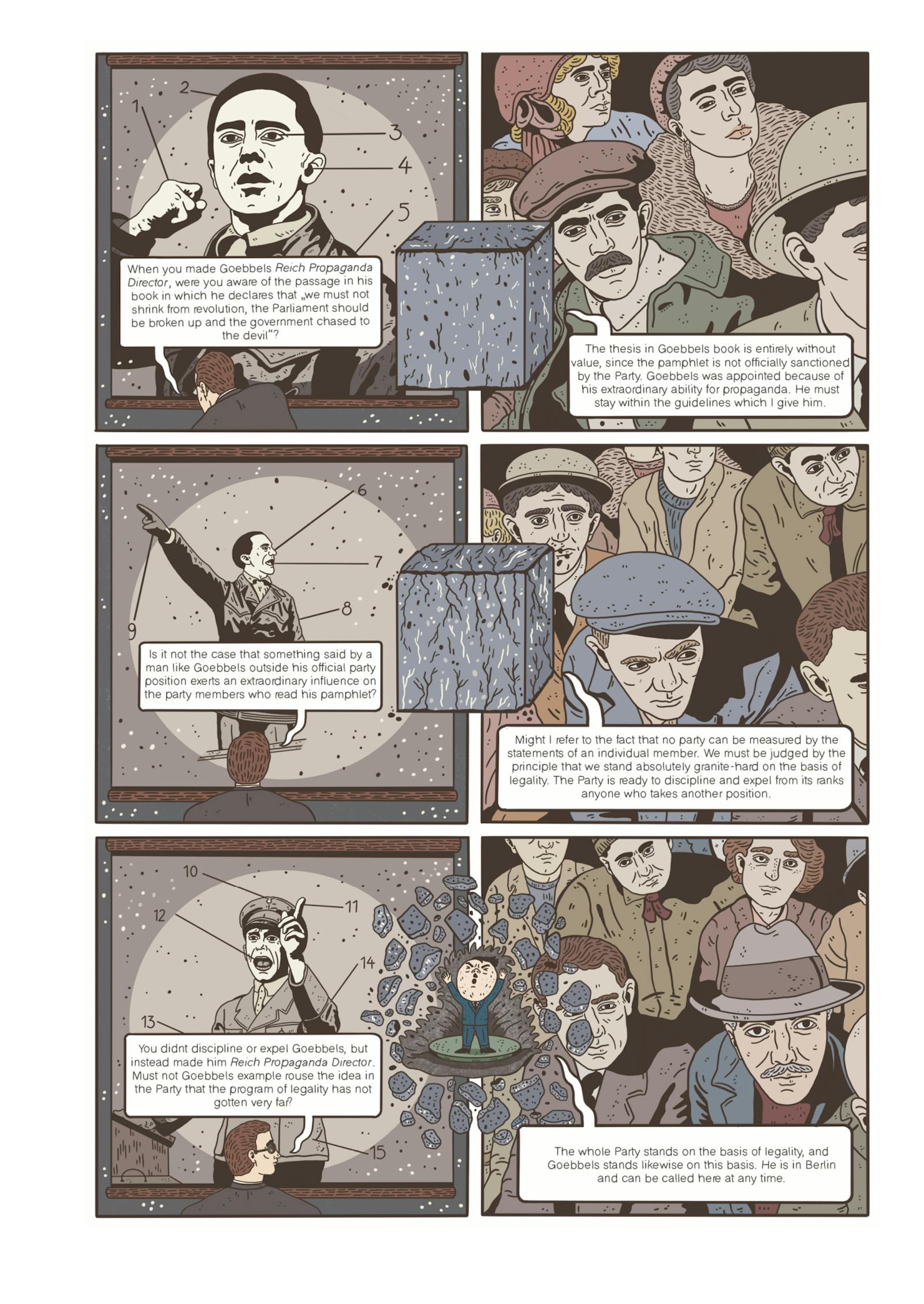

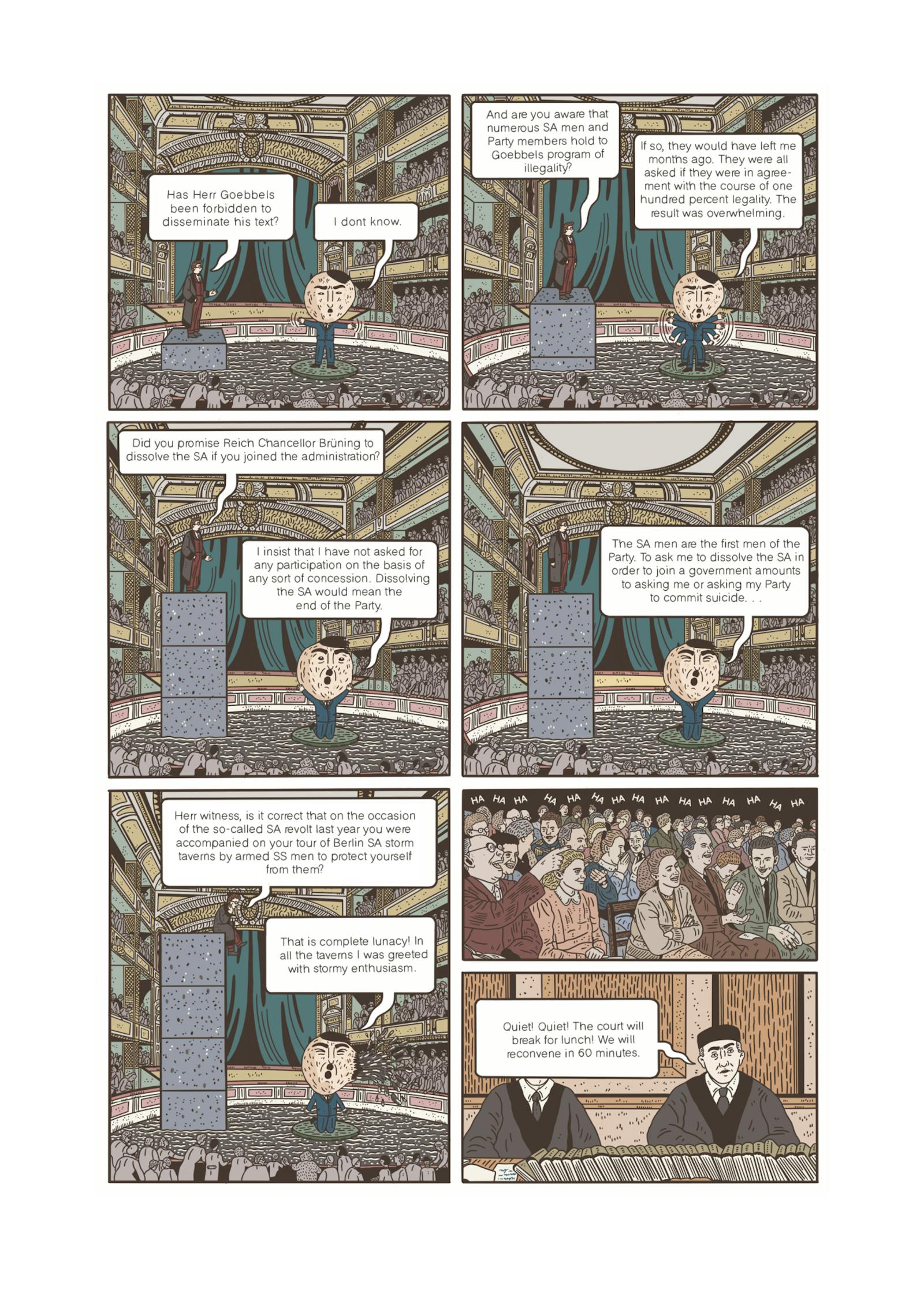

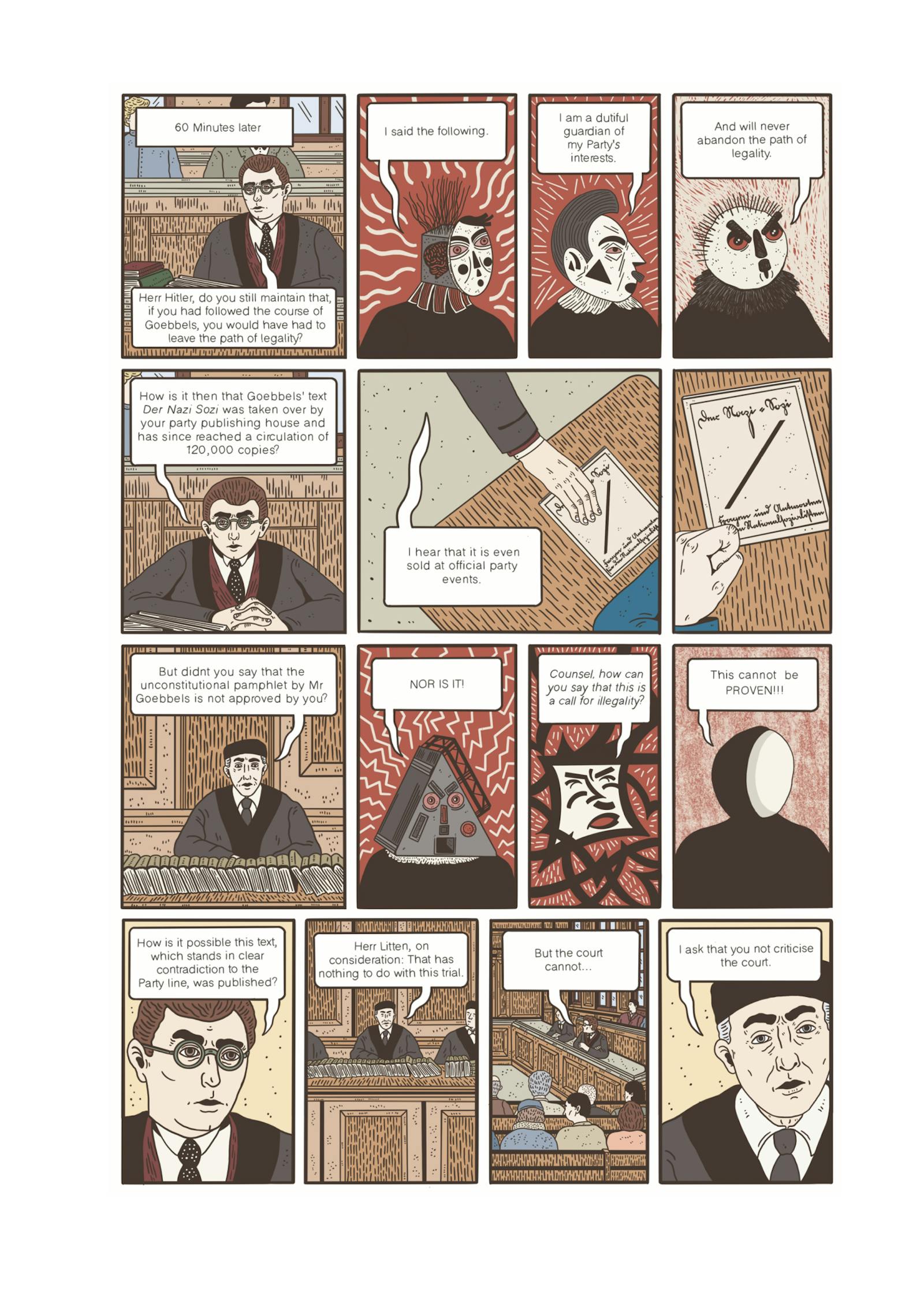

The graphic narrative opens up possibilities to personalise the historic reality, integrating the factual events with the emotionality of the people who had to live through them. Comics offer a collision of discourse and emotion, that usually refuse to go hand in hand.

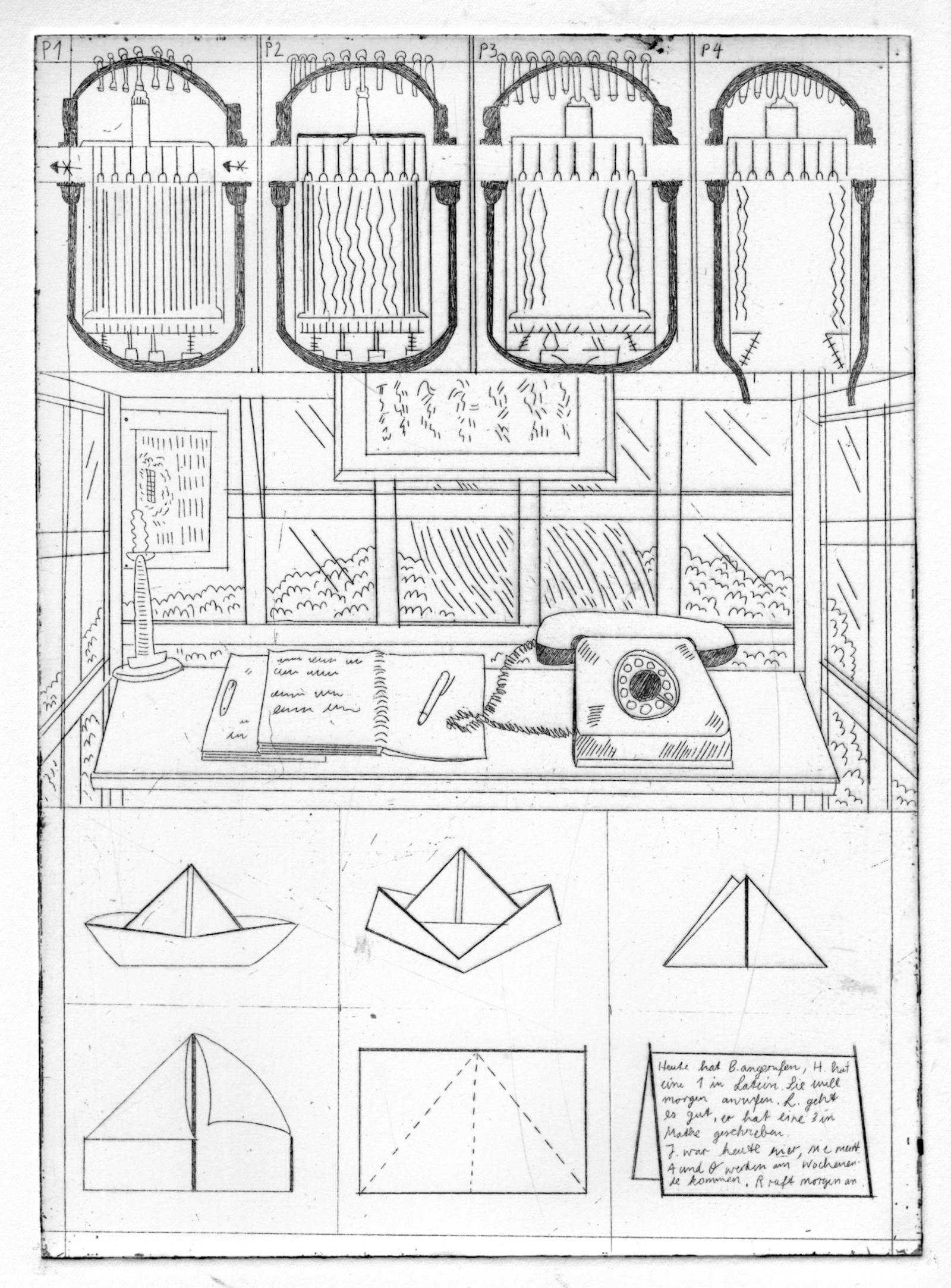

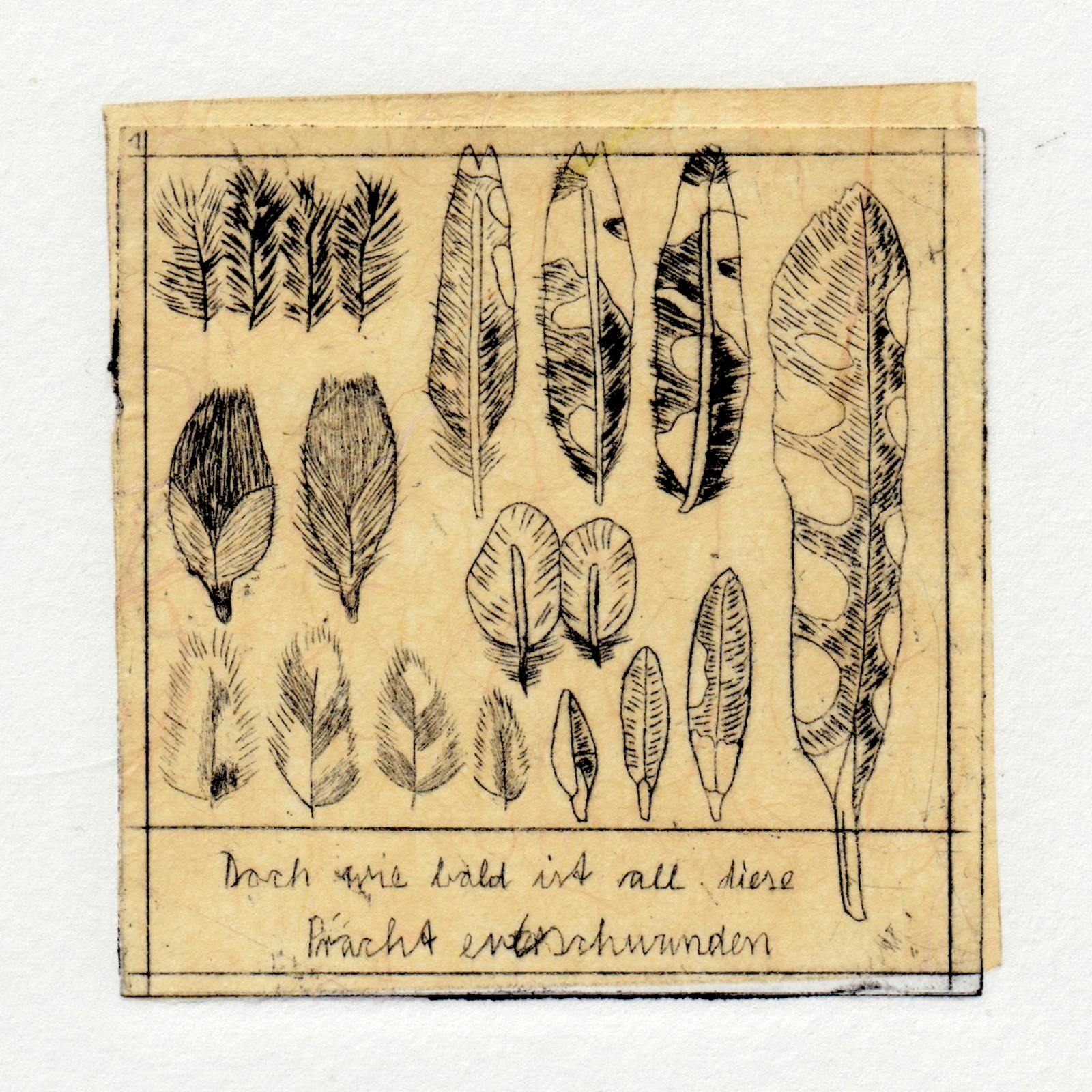

The Graphic narrative serves as a vehicle for personal expression and memory. Aestheticised Memory, as the most individualistic form of expression and testimony, can shape historical representation. Remembering traumatic history can be unbearable but through graphic narration it can be expressed and re-visited, even processed. Through panels, the graphic narrative expresses testimony and trauma as fragments. The borders of the panels display the event as a closed off entity, but at the same time the next panel builds on the one before. The frames relate to the past and the present simultaneously.

The graphic narrative is a commercial art form. Comics are reproduced millionfold. They are accessible for almost anyone and therefore crucial tools to reform our historical understanding. The graphic narrative in combination with political and historical investigation and aesthetic experimentation, lay bare new ways to critique the status quo. Mass produced art forms like comics, analyse who we are in the world, what we think about and how we act. With this they offer an inclusive, democratic dialogue and critical reflection on our normative historical discourses.

Revisiting our visual memory through abstraction is poetic in its own right but at the same time does something that the mere contextualisation and interpretation of history through written testimony cannot do. The visual reflection of our past creates emotionality, urgency and innovation to dusty discourses. The graphic narrative interrogates how we think about history and thus sheds a new light on underrepresented pasts. This needs to be embraced and recognised: Where the boundaries of the historical essay are limited, the graphic narrative strives to breach them by being inclusive and accessible, inherently political, confrontational and self-reflexive.

Additional info

Hannah Brinkmann is a graphic novelist, visual artist and researcher, looking into how personal witness accounts, the legal space and graphic narration can help to democratise and expand the historical discourse.

Hannah has given workshops about comics at institutions throughout Europe and the U.S., - among others at the Sitka Fina Arts Camp in Alaska, at the Berkman-Klein-Centre in Harvard, at the Lucerne School of Art and Design and the Bern University of the Arts - discovering that graphic storytelling can transcend all boundaries dealing with complex and difficult subject areas.

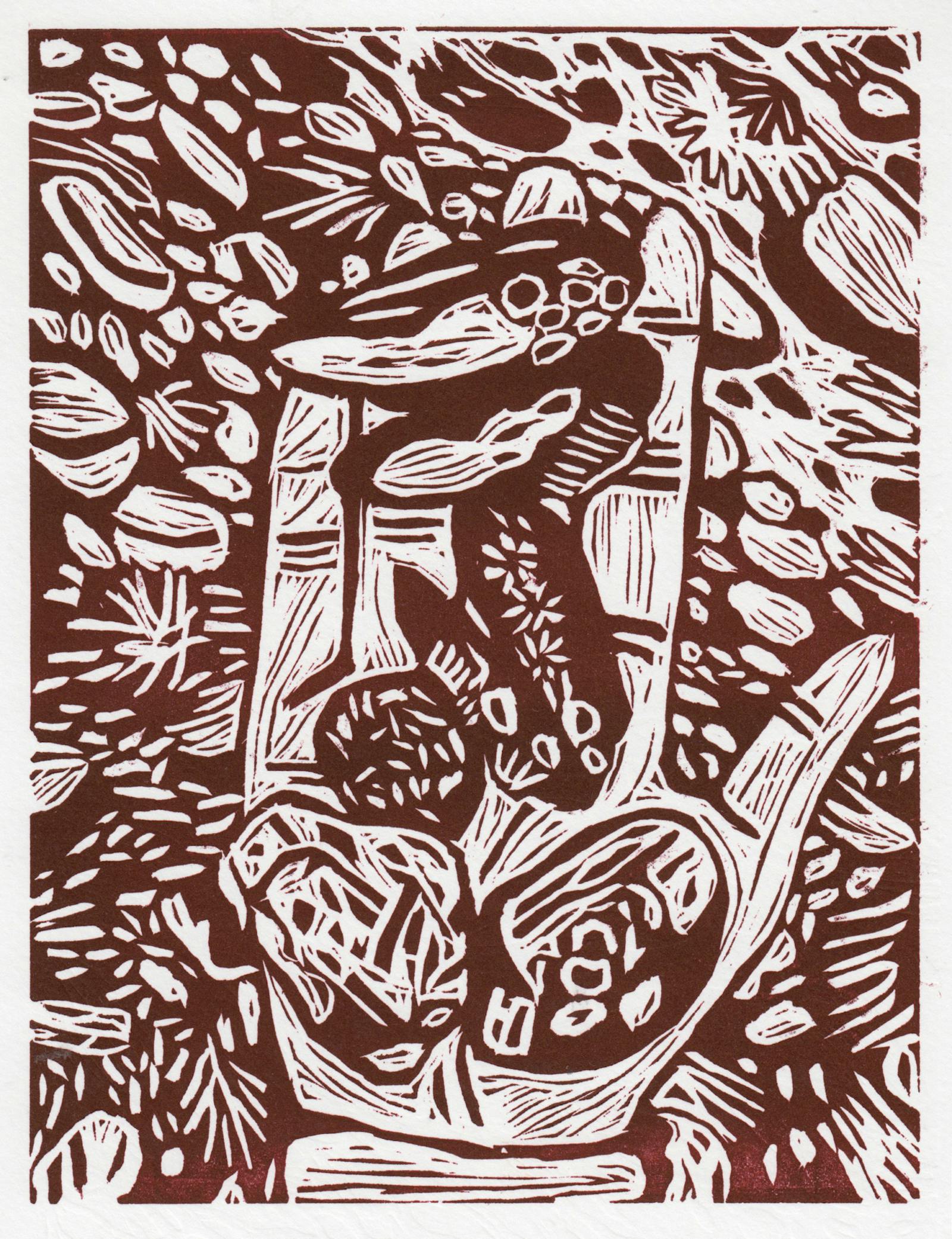

In 2015 Hannah founded the online magazine Odradek – the motive of the magazine is to tell non-fiction stories with little or no text, only with the expressive power of the drawing. Hannah has also collaborated with journalists to develop graphic documentaries that were published in German newspapers, working to establish graphic storytelling as an indispensable tool in our daily media consumption.

In 2018 Hannah was a summer-fellow at the Library Innovation Lab at Harvard Law School, where she went over West-Germany’s military and judicial history. At Harvard she also got involved with the Nuremberg Trials Project, where the project‘s researchers helped her to reflect on how military policy and judiciary decisions can shape our society and the individual citizen.

After publishing several non-fiction short-comics and working in comic journalism, her first long-form comic Against my Conscience (German title: Gegen mein Gewissen) was published in November 2020. It tells the story of her uncle Hermann who was a convinced pacifist and conscientious objector in West-Germany during the 1970ies and after being rejected by all conscience courts – an institution still in place during that time – he was forcibly drafted into the German armed forces. Shortly after that, he took his own life, causing a discussion about the legitimacy of the conscience trials.

In this work lies her deep conviction that Germanys post- war history should not be forgotten. On the contrary, she believes it is important to shed new light on it to learn from past mistakes and injustices. Since then, she has continually worked on her aim to firmly establish graphic narration as a medium to revisit historical topics – concentrating especially on forgotten or overlooked narratives. She thinks that only by really understanding the past we can grasp and alter our present.